In one way, I wish I did not have this book on my desk.

In a great many other ways, I am glad this book is in my life.

Deeply glad.

Profoundly glad.

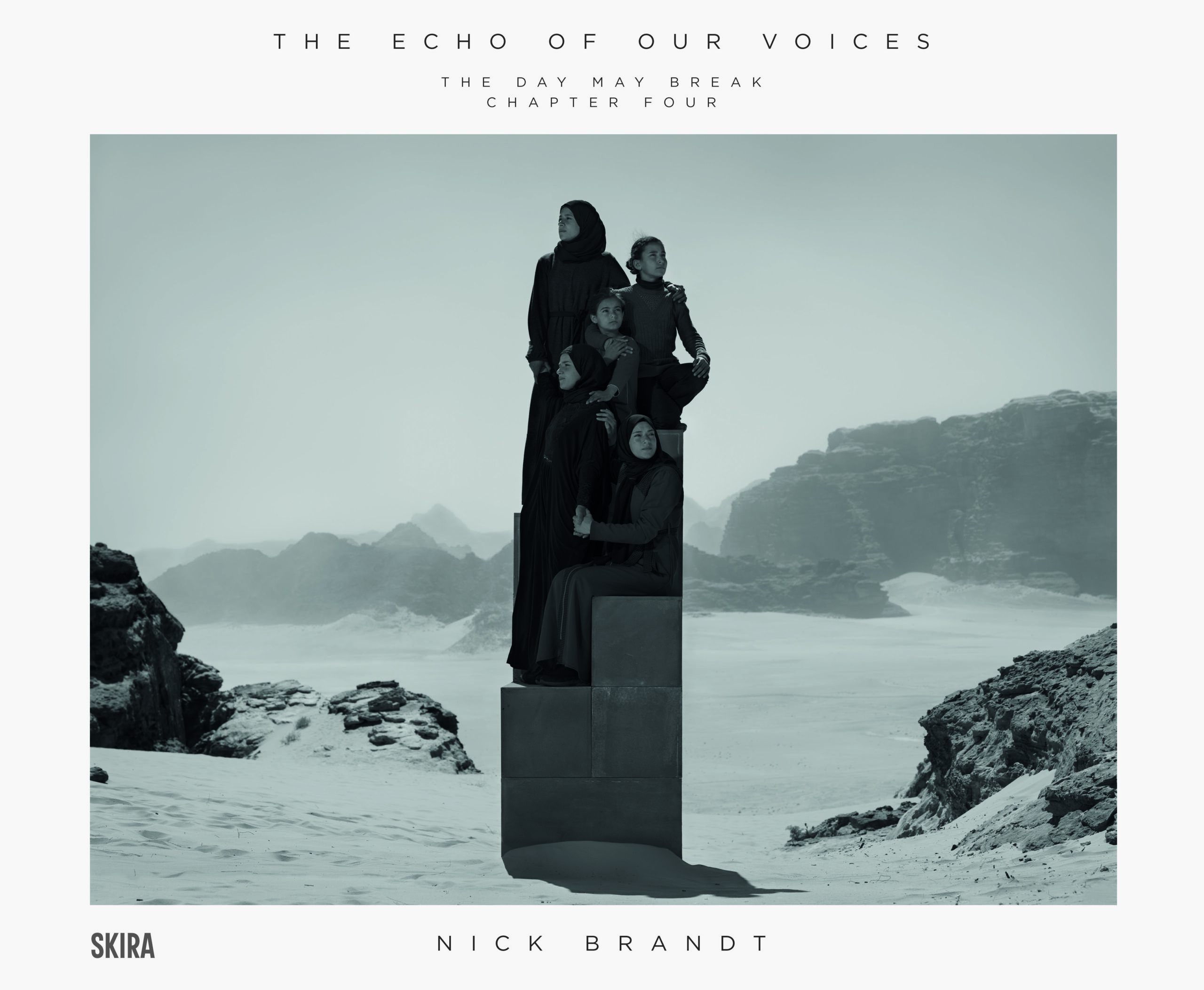

Nick Brandt – “The Echo of Our Voices: The Day May Break Chapter Four”

Published by Skira, 2025

Review by W. Scott Olsen

Photography, like any art, has the ability to strike deep into the soul. We’ve known this for a very long time, but every time it does, the moment is gasp-making, intimate, and fresh. Photography is always an act of illumination and revelation, yet sometimes it transcends these powers and claims new ground in our understanding of the world and of ourselves.

Nick Brandt is a photographer claiming new ground. His series The Day May Break is urgent, beautiful, necessary, and completely original. The project began as a way to work against climate change with a series of black and white portraits of animals and humans posed together in a type of visual duet—the animals rescued from sanctuaries and the people refugees. Fog fills every setting, as does sadness and warning. At the time, I’d never held a more troubling or wonderful book. Chapter Two (the second book) in the series continues the idea with a more emphatic call to action implicit in the images. Chapter Three took a look at one of the consequences of climate change—rising sea levels—and gave us portraits of men and women in commonplace settings and activities, such as riding a teeter-totter or sitting on chairs at a table, but in every case also underwater. From my point of view, each new book took photography into a new creative space and made the environmental argument with eloquence and insight.

This new book, Chapter Four, The Echo of Our Voices, goes intentionally to the opposite effect. As climate change creates rising sea levels, it will also make deserts more arid and severe. This book, again a series of portraits, is set in the Wadi Rum desert in the south of Jordan. Every person in the photographs is a climate or political refugee. According to Brandt in an introductory essay, Jordan is the second most water-scarce county on Earth, and the supply of fresh water per person has fallen 97 percent since the start of this century.

The Echo of Our Voices takes a different aesthetic approach as well. As Brandt writes:

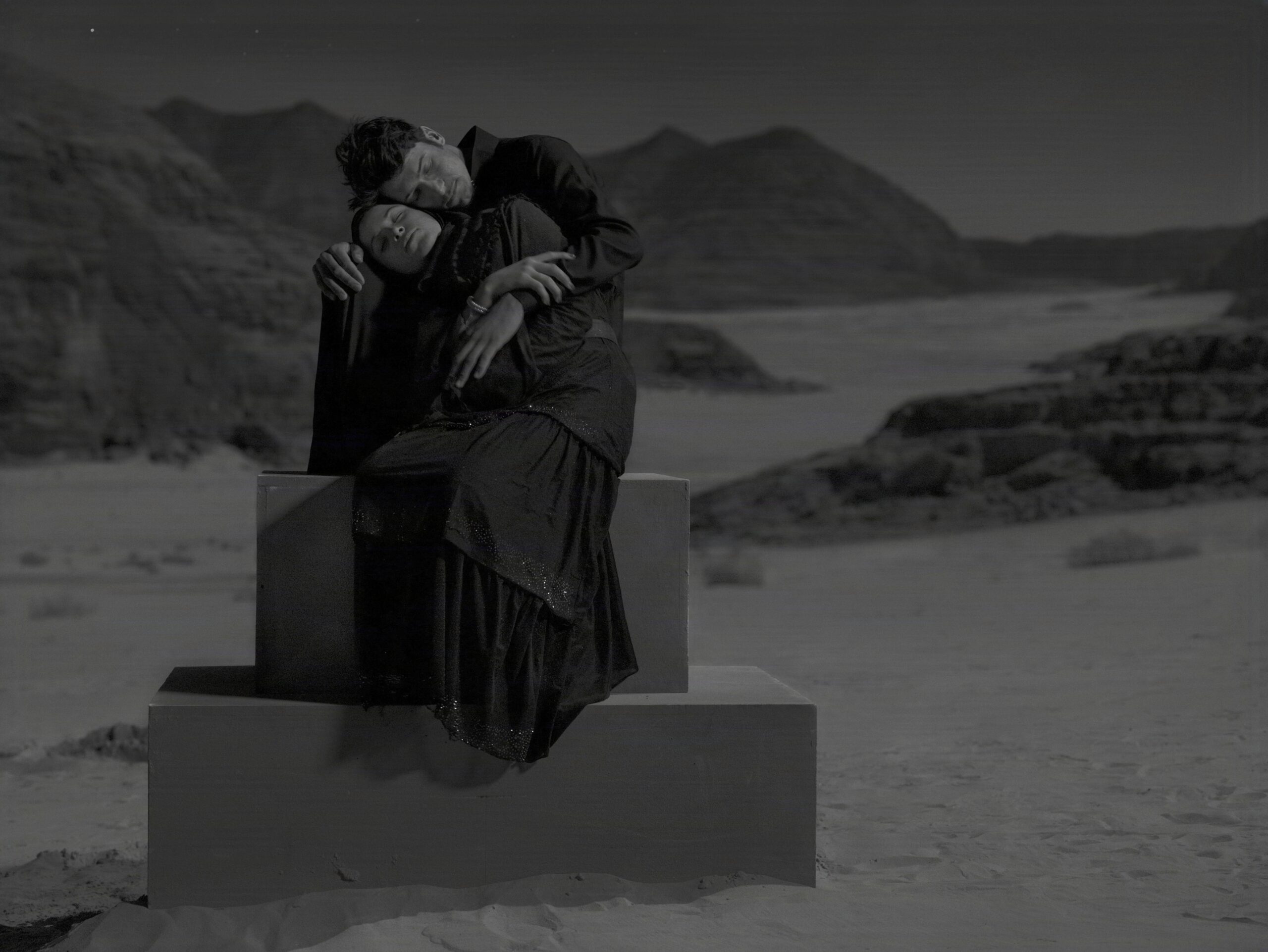

In the previous chapters, I had shown my subjects mainly in isolation, separated from almost everything that they knew, and usually separated from each other. There is certain desolation in those images. A disconnection. However, from the beginning, I wanted this chapter to be very different in tone, both visually and emotionally: a show of connection and resilience—that in the face of adversity, when all else is lost, you still have each other.

The reason for this difference? As things seem to grow darker with each passing year, I myself felt the need for a change of energy within the series.

The idea inside The Echo of Our Voices is to create a type of living sculpture. But to describe the images this way does not begin to explain their power and impact. Perhaps Tableau is better. Perhaps a visual parable. Perhaps something for which there are no descriptive words.

Brandt assembled a collection of boxes, set them in various places throughout the desert, with sand and rock and cliff and valley as backgrounds, and asked his participants, dressed in traditional garb, to stand on the boxes, then arranged them in metaphoric poses. Sometimes there is just one person on a box. Sometimes, it’s a mother and daughter or a father and son. Sometimes there are whole families. The boxes, and then the people, are vertically arranged so each composition seems tall.

Yes, it’s a bit like statuary. But here’s the thing. Statuary is static, removed from contemporary life. While a statue of Caesar, Pharaoh, or Beethoven may provide an opportunity for reflection and wonder, they lack immediacy. I don’t want to diminish their artistry, but our interest in them remains historical and academic.

The people on boxes in Brandt’s work are alive. They are alive now. They look at each other, and at us, with gazes that know what we know about the contemporary world. The arrangements demand an interpretation that begins with ideas of connection and responsibility. There is guilt and sadness and hope and love in every image, made real by the fact that these people share the same time on this planet as we do.

The Echo of Our Voices is a collection of black and white portraits set in the desert. They are contemporary and timeless. They are elegant and troubling. Highly constructed compositions, they nonetheless get to a truth of humanity like an arrow shot.

The book is blessed with several small essays that provide context and reaction to the images. In one, by Syrian novelist Samar Yazbeck, she writes:

I flip through the photographs with a trembling hand, one image after the next, beholding them with the reserve of a foreigner, of someone in exile. I notice each incredible moment, each clever shot revealing their deep subconscious terror….

The photographs keep coming, and I search for myself within them. I no longer think about writing; instead, I search my soul for outrage at injustice against humanity. Each photograph is a painting, and each painting is a small detail in a larger scene of gripping pain that the photographs attempt to address. When I stand before them, time itself stands still….

As I live with the photographs and reach the end, I ultimately realize that they contain a secret. These images are not only photographs; they draw from theater, film and poetry; they are the daughter of reality. Deeply truthful, and deeply imaginative. Imaginative for the intensity of pain and that silent cry, truthful as they are rooted in the refugees’ reality…

The thread that eludes so many who discuss the plight of refugees is love. Love is their final destination, their sole antidote, and the hope that keeps them alive, even while in limbo: suspended in space, waiting for the moment of return, their attire tells a tale of endless darkness, into which love prevents them falling.

In another brief piece, photography curator and editor Arianna Rinaldo writes:

Most of the people in these powerful, sculptural portraits wear traditional clothes that flow together with embracing arms and interlocked hands. They become one. The vision of the whole is striking.

Then our glance begins to focus on the individuals, the parts of this unity. It lingers on faces, eyes open or closed, looking out or at the camera, caressed by the wind or the moonlight. We are taken in swiftly but softly and we wonder what their stories are, what they were thinking while being photographed, what they might be thinking now as new opportunities might arrive for their families’ future….

The Echo of Our Voices is a monument to unlimited aspiration and unwavering kinship, where center stage is held by humans bound by family ties, a fierce destiny, and now a powerful voice that must echo beyond these borders.

Brandt himself writes:

I researched other countries around the world with deserts, but I kept coming back to Wadi Rum desert in the south of Jordan. It was the verticality of the mountains emerging out of the desert plains and dunes that captured my imagination. It was the place that bore the most similarity to the visual inspiration of Gustave Doré’s extraordinary Bible engravings…

These are people who lost their homes, their way of life, their communities, their land, everything. Now all they have is each other. It seems to have given them a strength and togetherness in the face of such adversity. There was, is, a grace and humility to them, that perhaps also made them connect more with the principle of the project.

Finally, a brief word about book arts. The Echo of Our Voices is a physically outstanding project. Printing black and white images is near the top of the difficulties in photographic arts, and this book is a master class in what can be achieved. Also, while the first three volumes of The Day May Break are identical in size, this one breaks that tradition a little bit by being slightly wider and slightly shorter. The invitation here is to open the book and let it linger on a table or desk, to spend time with each image without the implied push to turn the page. As with the earlier volumes, every moment spent on every page is a moment well spent, not only for aesthetic appreciation, but for a moral self-examination as well.

Yes, I wish there were no climate change. I wish there were no refugees. That’s what I meant when I said in one way I wish this book were not on my desk. But we live in a wonderful as well as troubled world, and I am grateful for Nick Brandt’s vision.

A review of Chapter One is here.

A review of Chapter Two is here.

A review of Chapter Three is here.

A note from FRAMES: Please let us know if you have an upcoming or recently published photography book.