The 1920s and 1930s were a remarkable period for heavy industry in the United States. Mass production of goods such as rubber and steel and consumer products like automobiles and radios reached unprecedented levels. New technologies, most notably assembly lines and the application of electric power, allowed not just a greater volume of production but economies of scale that transformed society as a whole. “Fordism” – the label given to these new regimes of mass production and the culture to which they gave rise – both promised a new era of general prosperity and foreshadowed a world of uniformity and alienation. Numerous art forms, from the industrial murals painted in Detroit by the Mexican Diego Rivera to the movies of Charlie Chaplin humorously depicting regimented factory life, played off of and commented upon the promise and dystopian possibilities of endless manufacture. Photography, too, contributed to the artistic effort to make sense of the novelty of mass production. Indeed, this period saw the making of some of the most powerful visual images of industrial life ever created.

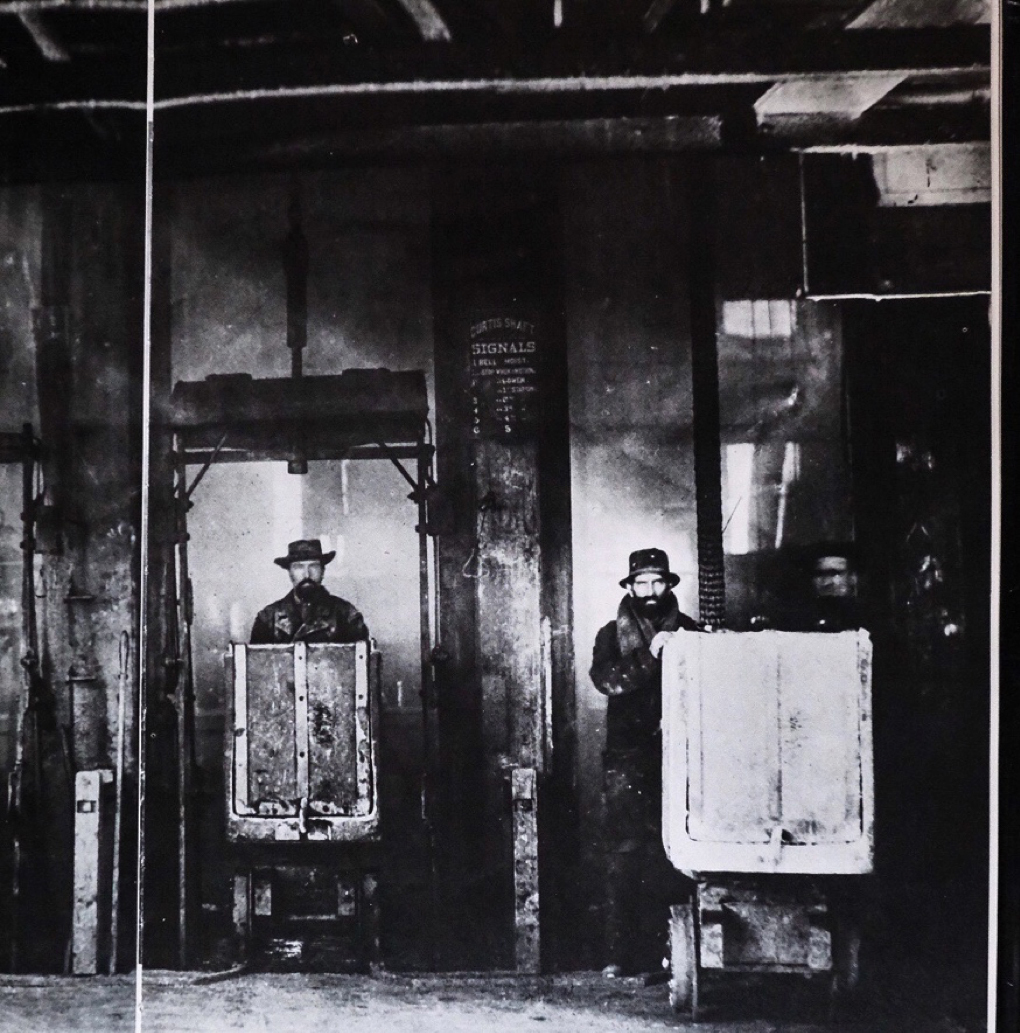

In order to understand how revolutionary these images of industry were, one needs to go back to an earlier period in the history of photography since, of course, photographers had produced pictures of industry well before the advent of Ford and Fordism. Mid-nineteenth century photographers such as John Mather and Timothy O’Sullivan made superb photos of mining, oil drilling, and metal production at the start of the industrial era. Just after the turn of the century Alfred Stieglitz produced one of his first great images, “The Hand of Man,” a homage to the railroad and its transformation of the landscape (see figures 1 and 2). However, these sorts of photographs tended to be shot outdoors and rarely depicted actual labor or production processes, in part because of the limitations of camera technology at the time. Even Stieglitz’s capture of a steam locomotive pushed the boundaries of long exposure on glass plates to make the now classic photograph.

Industrial photography began to flourish when corporate management made an early twentieth century pragmatic turn towards the medium, using cameras for surveillance and to document technological innovation. In the hands of management, photography’s most important role involved studying the labor process with an eye towards realizing greater efficiencies of time and movement. In fact, the new field of “scientific management” turned to the camera while still in its infancy. Building on the work of earlier photographers who sought to use multiple exposures to better understand body mechanics, corporate industrial relations experts realized that photography could measure with precision the simplified movements of assembly workers, allowing them to trim wasted motion and realize greater efficiency and output.

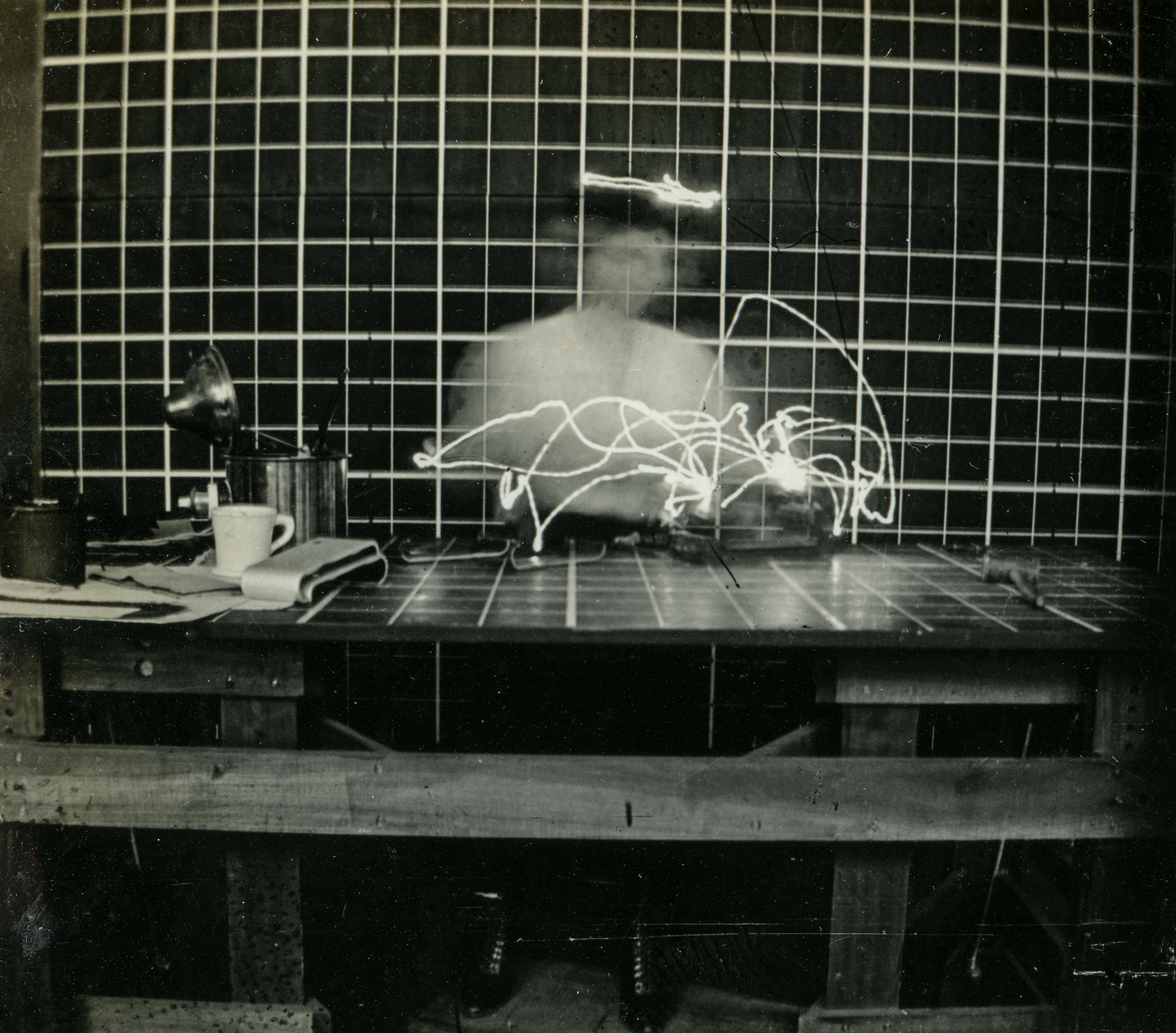

No figure played a more important role in marrying photography to scientific management than Frank Gilbreth, who began using the camera while in the thrall of efficiency expert Frederick Winslow Taylor (whose famous first study focused on coal shoveling) to isolate the movements of a skilled bricklayer and then reconfigure them in a “better” way. Gilbreth soon moved beyond Taylor, who used only a stopwatch, and onto the shop floor with what he coined “industrial chronophotography.” This involved attaching a small light to an assembly worker’s hand, making a long exposure, and then studying the revealed motions with an eye toward eliminating waste. Inefficiency expressed itself in a tangle of ragged lines: the fewer the lines the less wasteful the motion (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Frank Gilbreth, Motion Efficiency Study, 1913 (Courtesy of Purdue University Libraries)

Gilbreth’s photographs treat workers as little more than machines, or cogs in larger machines; they appear in his images as not as full human beings but only as abstract representations of labor – an effect visually heightened in most of the photos by the blurred faces and arms produced by long exposure. Interestingly, many of the images used by corporations to promote themselves and document new technologies either pushed workers outside the frame or rendered them as extensions of machines. For instance, consider figure 4, shot by an unknown photographer in Bethlehem Steel’s wire rod rolling mill in Johnstown, Pennsylvania: a shop floor utterly devoid of steelworkers as if the rods somehow could make themselves. Or look closely at figure 5 which depicts a “modern machine tool” at Midvale Steel in Philadelphia and shows a workman’s disembodied hands manipulating the device’s levers.

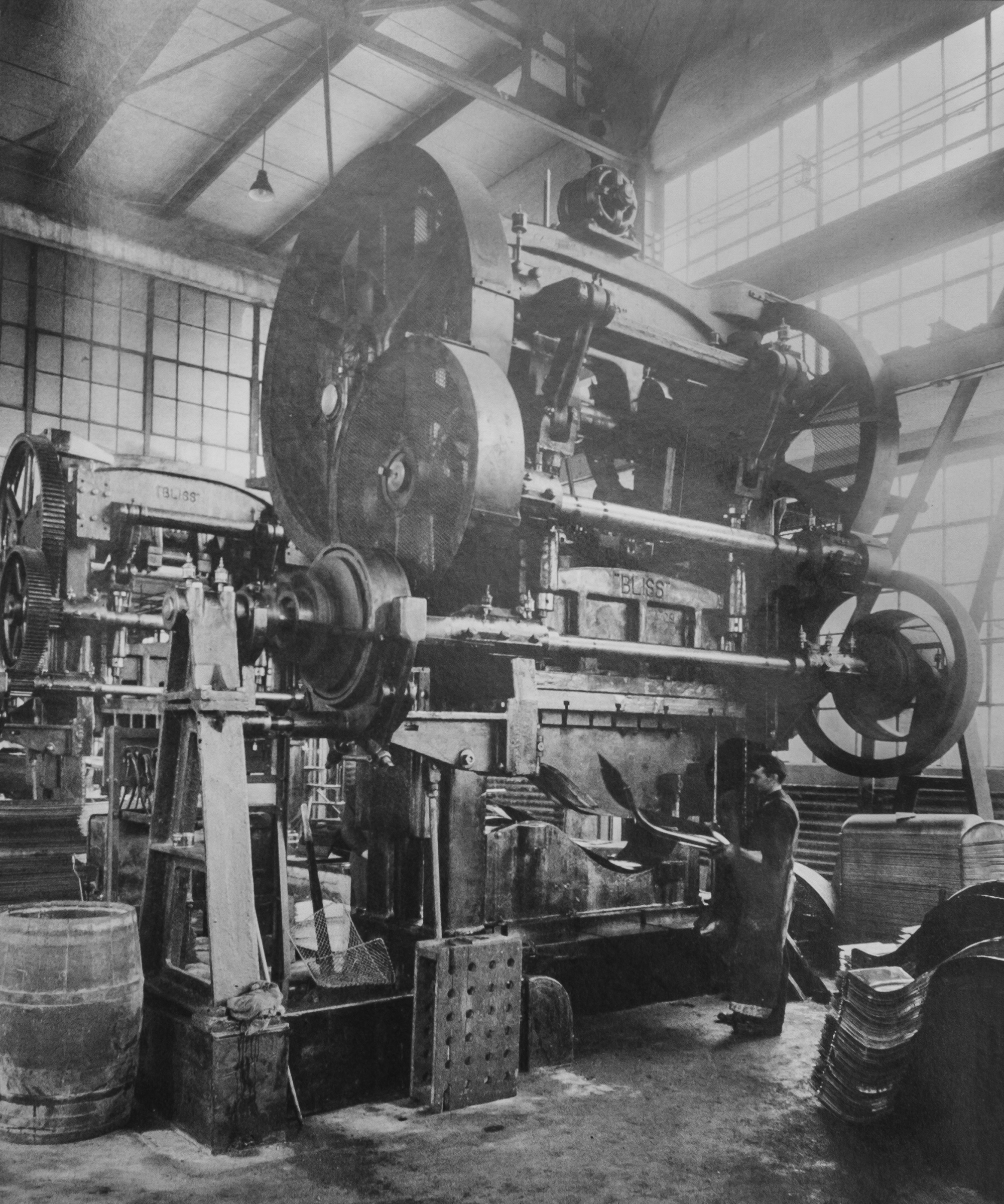

Like much of the public, photographers were fascinated by the sheer scale of industrial production and the sophistication of new precision technology, especially in metal work. The same photographer, John Mudd, who shot the levers at the Midvale works, also turned his camera to the drama of smelting. Mudd’s “The Giant Heat,” from a different part of the same plant, shows several tons of molten steel being heated in a suspended giant bucket dwarfing five workmen who are seen only in silhouette, backlit by the sparks of the heat (figure 6). Similarly, an unknown cameraman in 1918 photographed a Bliss punch press at Milwaukee’s Allis-Chalmers locomotive works (figure 7). The press was used to stamp metal by applying hundreds of tons of steam-generated pressure to a sheet placed above a die. The focus here is on the magnificent piece of heavy equipment, though a close inspection reveals a lone worker removing a curved piece of stamped metal from the maws of the machine.

The advent of the assembly line and its rapid adaptation in the first decades of the twentieth century coincided with other developments that allowed industrial photography to leap top new stage of sophistication. To start with, one of Fordism’s key innovations was the use of electricity instead of steam or coal-generated heat. This, along with new precepts of industrial design and architecture meant that both natural and incandescent light brightly illuminated shop floors that previously had been bathed in shadow. The era also saw the introduction of rolled gel film and smaller cameras that allowed more precise control of aperture and exposure. The results were breathtaking, both in terms of documenting mass production with high quality photographs and more abstract images of the Fordist factory.

These new photographic forms and frontiers are best illustrated if we turn to the automobile industry and the Ford Motor Company itself. Vertically integrating its business operations in the 1920s, the company hired a talented group of staff photographers. In addition to shooting promotional material for Ford, these photographers found the symmetry of the assembly lines and sleek architectural forms of new plants such as the River Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan, an irresistible lure. Interestingly some of the best shots are not variants of the ubiquitous automobile chasses rolling down the line, but the intricate work of small motor assembly (see figure 8) or glass inspection (see figure 9).

Both photographs are superbly composed images. The assembly lines diagonally bisect both frames, and intent workers are shown concentrating on their labor. In the first picture the slightly bowed heads of workers form lines parallel to the bristling wires of the small motors, and in the second the far edge of the conveyor table underscores the leading lines of the photograph while the rectangular windows on the left mirror the workers’ backs. Moreover, in contrast to the many of the earlier illustrations in this essay, these photos are technically accomplished in terms of exposure, clarity, and focus.

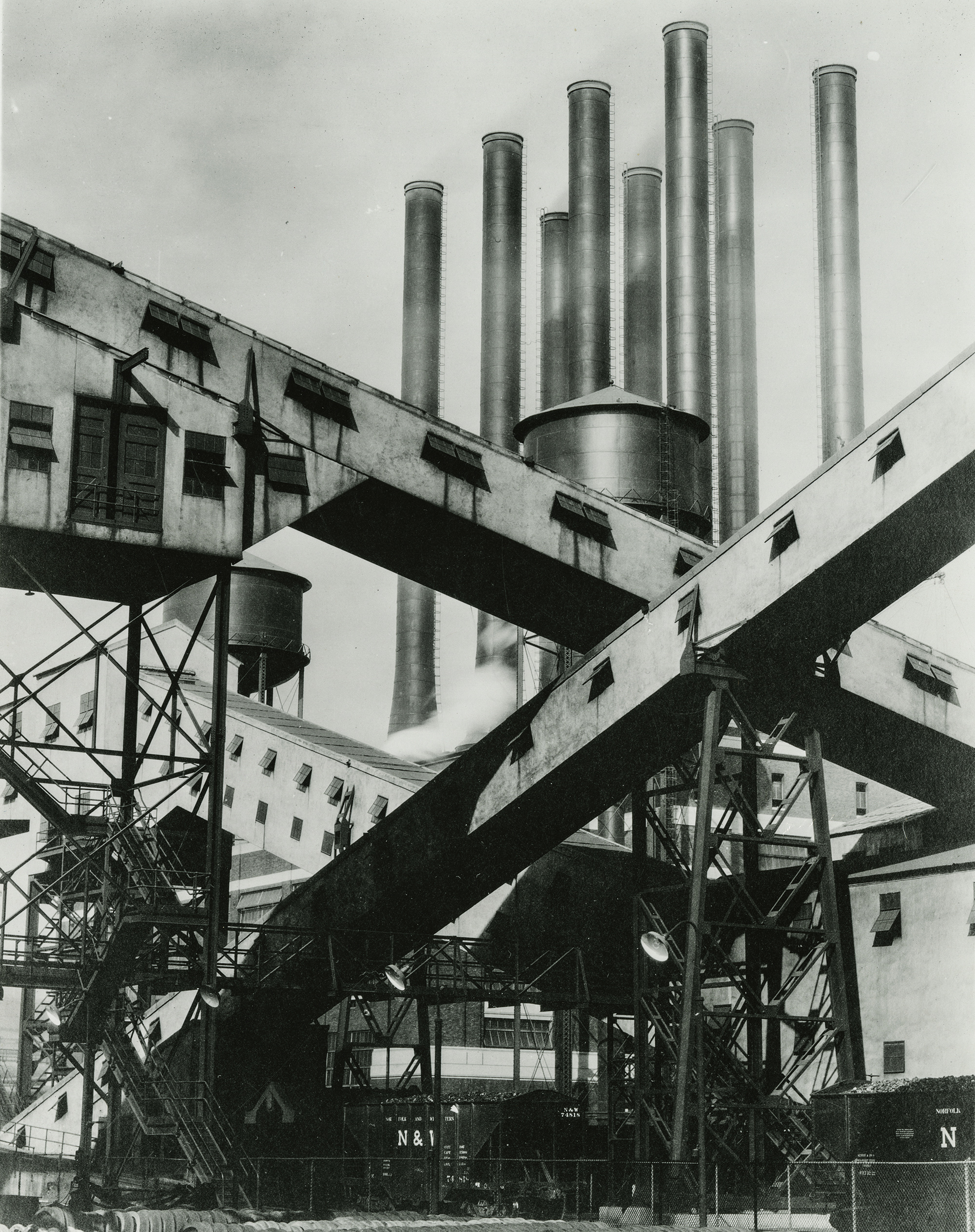

The facilities Ford constructed in the late 1920s were architectural paeans to modernism. Relying on the visionary designer Albert Kahn (who also secured commissions with Packard and General Motors), many of these plants rewrote the rules of industrial aesthetics. It was no surprise that they attracted photographers who found their geometric patterns, clean lines, and gleaming construction materials symbolic of the age. Charles Sheeler, who earlier in the 1920s collaborated with the photographer Paul Strand on an avant-garde film on urban modernism, visited Ford’s River Rouge complex at the end of the decade as part of a team of artists working to promote the release of a new model car. Though best known for his painting and drawing, Sheeler’s photograph, “Criss-Crossed Conveyors,” captures the ideals of power and productivity at the heart of industrial modernism (see figure 9). The massive plant itself, devoid of workers in almost all the photos Sheeler shot and the canvases he created, formed his sole subject and later inspired similar studies of structural design in ships and skyscrapers.

A painter first and foremost, Sheeler was fascinated by photography’s precision, a quality that he called its “exactness” that work in watercolor or pencil found ever elusive. He also found that when industrial design was his subject, black and white photography allowed him to easily move from representation to abstraction.

Indeed, the creative transformation that Sheeler noted, from the mundane everyday view to striking art, is part of the enduring magic of photography. In the realm of industry, it is magic indeed to take the noise and grime of the modern factory and create something of beauty. To do so skillfully using a camera with precision crafting and high built quality to produce an enduring photograph allows one to play the magician as well. In this sense, perhaps we should understand photography as a quintessentially modernist medium.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rick Halpern is an historian and photographer based in Toronto. In recent years he has been writing about the history of visual culture, especially photography, and the way it has shaped our understanding of identity and place. His photographic practice focuses on three main themes: urban life, travel, and food.

C Paul

February 24, 2023 at 07:18

Absolutely loved this – such great photographs. The B&W film hasn’t changed drastically since then. The film cameras didn’t change that much since then, really. These pics are all about composition, lights, and shadow – but I guess every photo is. These are masterful.

Jana Apergis

February 29, 2024 at 16:47

I am a photographer and photobook enthusiast. Born in Detroit in the 60’s, my exposure to industry as an art subject was low key. I’m certain I saw Diego Rivera’s mural of Detroit factory workers in the DIA (“You Gotta Have Art”) as well as other photos from the car factories.

My appreciation however evolved as I viewed images from Margaret Bourke -White, Lewis Hine, Dr Paul Wolff, and the Bechers.

I love their skillful composition with a seemingly “boring” subject … how they capture the beauty of metal’s sheen using monochrome film.

Some have taken this further by exploring the decay of such paramount factories in Detroit, East Germany, Russia etc

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder”