Photography and the twentieth century city grew to maturity together. Put another way, “modernity” came to be defined by urban life, and the camera, more than any other instrument, made the vibrancy and visual culture of the city available to a mass audience. Postcards, illustrated journals, and popular magazines supplied photographs to readers who, though they might live in rural areas, came to understand the city through these images. At the same time, city managers and reformers used photography as a tool with which to address many of the challenges associated with the modern city: municipal planning and development, slum clearance and urban renewal, and crime and delinquency.

Like several other North American cities, Toronto, placed photographers on the municipal payroll early in the twentieth century. Unlike many other places, Toronto fortuitously employed a set of truly remarkable photographers whose work has been meticulously preserved in the city’s official archives. Arthur Goss began a thirty-year stint at the Department of Public Works in 1911, producing more than 15,000 images for the city; Arthur Beales was employed by the Harbour Commission in the same period; and Alfred Pearson worked for the Toronto Transit Commission. Their collective output documented Toronto in an exciting extended period of growth, one that saw it evolve from a sleepy outpost of the British Empire to the country’s leading metropolis.

When Arthur Goss began his work for the city, its population stood at only a quarter of a million people. His early work is notable for the photographs of large infrastructure works such as the building of the Prince Arthur Viaduct that connected the city’s main east-west artery, Bloor Street, to the rapidly developing area east of the Don River (see figure one) and the construction of Union Station, a rail hub in the heart of the burgeoning downtown adjacent to Lake Ontario. A key feature of the modern city was its size and scale, and Goss was able to make a visual record of the process of growth, always paying careful attention to the technology and labor that made this possible.

Although the city continued to dispatch Goss to shoot other large municipal projects (his early 1930s photos of the giant R.C. Harris Water Filtration Plant later inspired the novelist Michael Ondaatje, who included a scene set there in his 1987 In the Skin of a Lion, in which Goss himself makes an appearance), once established in his job he was able to wander the streets, shooting what he pleased and processing scores of images each week in his Department of Public Works darkroom. All of this was covered by the city’s generous budget, although periodically over his long career irritated council members raised eyebrows and grumbled at the expenses incurred. Perhaps feeling grateful for this support – truly unique for an early 20th century photographer — Goss was repeatedly drawn to City Hall itself as a subject. Designed by Toronto architect Edward James Lennox, the stone building with ornate fixtures, including a clock tower and fierce gargoyles, dominated the top of what then was called Terauley Street (now Bay Street), the city’s financial district. Figure two, below, shows three workmen posing next to one of the giant gargoyles. It also shows of Goss’s exceptional technical and creative skills. Everything from the composition to the use of light and shadow is perfect, and one wonders where, exactly, Goss stood with his box camera and its heavy glass plates when he made this photograph.

A hallmark of the modern city were streetcars and busses, followed later by trams and, eventually, subways. Horse drawn carriages, essentially no different from transportation in farming areas, gave way after World War I to automobiles. Indeed, along with tall building motorized transit was the feature of urban life that first time visitors never failed to comment upon. Alfred Pearson, the photographer employed by the Toronto Transit Commission (formed in 1921) captured these symbols of modernity with a systematic and technically proficient style. For instance, in April 1923, he shot the complicated juncture of King Street, Queen Street, and Roncesvalles Avenue as a maze of track, some 2,240 feet in length and containing 266,185 pounds of steel was installed. Laborers, supervisors, and onlookers fill in his frame, as does an empty streetcar and a series of billboards selling mass consumer goods (see figure three).

Always attentive to the surrounding panorama, many of Pearson’s photographs rise above the simply utilitarian level by the inclusion of pedestrians. For example, a month after shooting the chaotic tangle of track in Roncesvalles, Pearson stood at a busy construction scene several blocks to the east, his camera aimed at workmen laying temporary track as Dundas streets was widened to accommodate an ever-greater volume of traffic. Several of the men look directly at the camera, but what makes this a stellar image is the smiling boy, hands in pockets, shirt buttons gleaming, walking by the job site on the far right of the picture (figure four).

As a working port, and one that saw its shipping traffic grow exponentially in the early 20th century, the Toronto Harbour Commission was constantly documenting the industrial waterfront. Arthur Beales, its prolific photographer, also had a fine eye for people and play. His photos of beach pavilions, swimmers, and sailors capture Edwardian summer recreation often in stunning ways. His shot of a crowded 1920s beach in the city’s west end (figure five) is notable, not just for the mass of humanity packing the sand, but for the men’s straw hats and suits and the women’s full-length dresses. Lake Ontario also provided an excellent vantage point from which to photograph the city’s changing skyline, not least because many of the grander new buildings were clearly visible from the water: the Royal Fairmount Hotel, Union Station, and the Canadian National Exhibition’s Main Pavilion. Indeed, postcards of the skyline – many provided by commercial photographers in the city – gave tourists a way of sharing urban wonderment with family and friends back home.

Throughout the early decades of the twentieth century a host of splendid commercial photographers complemented the municipal trio of Goss, Pearson, and Beales. Easily the most important of these professionals was William James, an Englishman who immigrated in 1907 and immediately set to work in his new home. Although James earned a living making portraits in his studio, he excelled at what we now would label street photography. He seems to have been a peripatetic presence in the city, wandering the streets and alleys. His most powerful and enduring work depicted immigrant life, first in Toronto’s notorious First Ward and later in the largely Jewish Kensington Market area. His 1911 photograph of a Jewish rag picker, pulling his heavy haul in the snow, is as enduring classic image. So, too, is his 1926 photo of a woman carrying a just purchased live chicken with a horse-drawn delivery wagon, bicycle boy, and Hebrew lettered store signs in the background. Both pictures convey captivating “stories of the street” (see figures six and seven) but also communicate to a native audience an exotic tone of the new foreign language speaking immigrants in their midst.

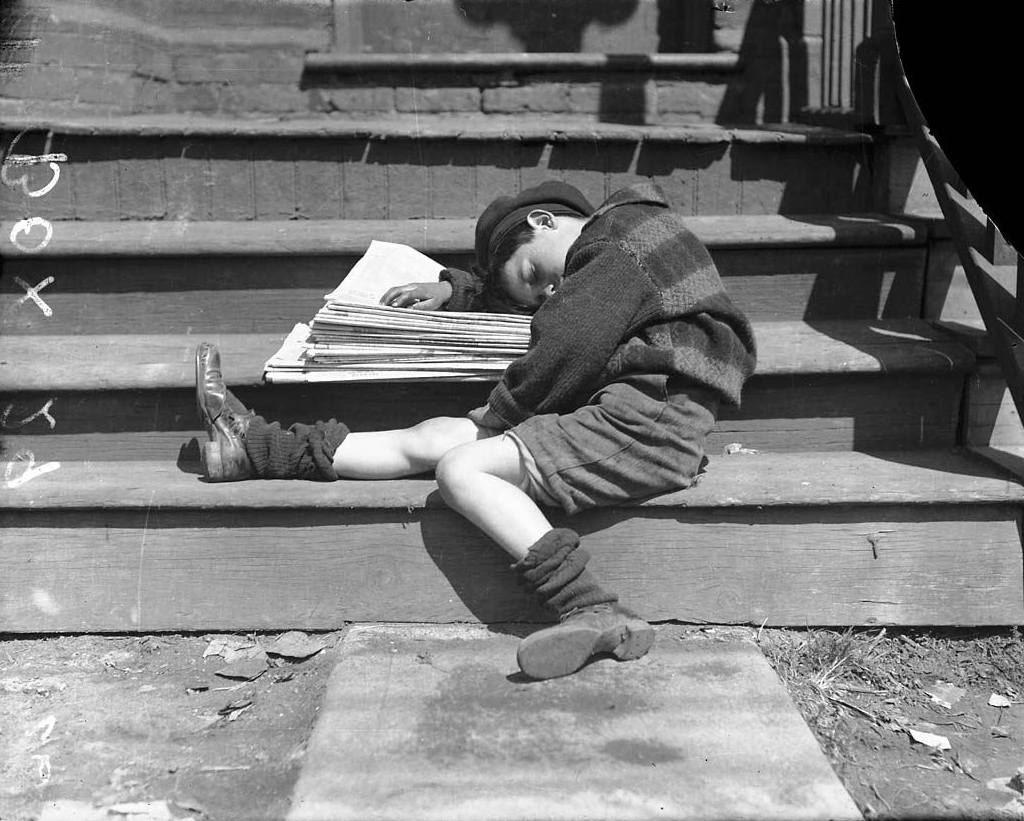

Fully deserving of mention in a discussion of Toronto’s twentieth century photographic culture are the photographers Nat and Lou Turofsky, who ran Alexandra Studios on King Street for nearly five decades. As with William James, commercial work provided their bread and butter. However, in the case if these two brothers a comfortable income flowed in from shooting weddings, taking snap portraits at the city’s annual summer fair, the Canadian National Exhibition, and covering sports events (Nat later became the official photographer of the Toronto Maple Leafs). Often overshadowed by the Turofsky’s commercial success is their more personal photographic work. Like James, some of their street photographs are striking captures of urban life, such as Lou Turofsky’s 1930 image of a sleeping newsboy, limbs akimbo, with his pile of unsold papers beside him (figure eight), or his beautifully angled shot of his brother at work, bellowed camera in hand, in front of a tall downtown building with ornate stonework (figure nine). The Turofskys had a remarkable feel for both the visually dramatic (certainly evident in their sports photographs) and the decisive moments of everyday life.

If images of poured concrete, structural steel, urban transit, high rise buildings, crowds, immigrant newcomers and street waifs signalled a vibrant urban metropolis, one that epitomized modern times to a far flung audience of what remained, even in the 1930s, a predominantly rural nation, the city also had a less appealing underbelly. Urban growth also meant overcrowding and the emergence of slums. Waves of newcomers could seem threatening and not merely exotic. Toronto’s elected officials grappled with a full range of social problems and, not surprisingly, they deployed their municipal photographic staff as they sought to make sense of these challenges and potential identify solutions to them. As historian Sarah Bassnett has observed, reformers had used pictures in the past, but the heightened problems of the early twentieth century allowed photography to emerge as an important tool in the arsenal of local government, one that generated a heady mixture of both knowledge about the city’s more unsavoury aspects and, somewhat paradoxically, heightened anxiety about them.

Health concerns were at the top of city officials’ reform agenda. A 1910 typhoid epidemic and alarming rates of other infectious diseases, coupled with a growing awareness of the squalid living conditions of the immigrant neighborhoods, prompted the City Council to authorize a full-blown investigation into slum conditions early the next year. The enquiry admirably adopted emerging sociological techniques and also made ample use of photography, “borrowing” Arthur Goss from the Department of Public Works for several weeks. His shots of overflowing latrines, dilapidated housing stock, and overcrowding appeared in the final report as factual evidence, captioned with matter-of-fact descriptions. Released to the local press, the report led to a wave of sensational journalism, not just acquainting the city’s respectable residents with a host of major problems in their midst, but also stoking middle-class fears of contagion and immorality.

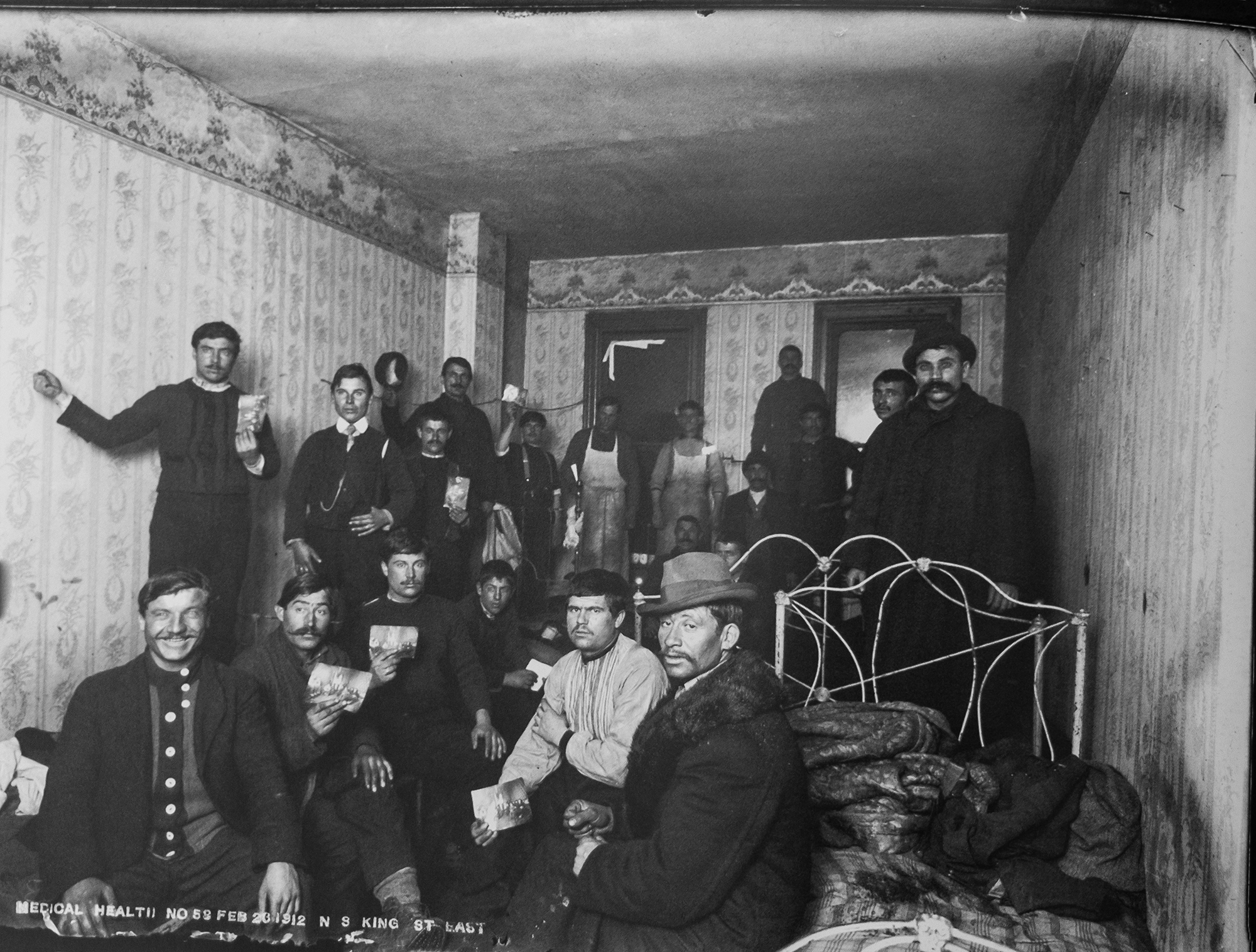

Goss’s photographs for the 1911 report are far from his best work. But two years later, following the implementation of several public health initiatives, a second survey was mounted. This one allowed Goss to shine, not because he could shoot at a less demanding pace but also because Toronto joined with several other North American cities to participate in the new Bureau of Municipal Research, headquartered in New York, and Goss knew his photographs would receive wide circulation. Many of his pictures produced for this project are noteworthy and reminiscent of the best work of Jacob Riis or Lewis Hine (1). A good example is his shot of a crowded room in a boarding house (figure ten) that shows seventeen immigrant men, identified as Bulgarians, crammed into an area clearly meant for two or three people. It is a compelling image packed with interesting features. Some of the men are smiling; others glance suspiciously at the camera; still others affect a deadpan visage. A few wear overcoats and hats, while two figures in the back have their work aprons on. Unlike Riis, working earlier in the century and using a crude flash mechanism that created an unfortunate “Frankenstein effect,” Goss opted for a long exposure and, evidently, had established enough of a rapport with his subjects to hold their gazes and get them to pose without moving.

Yet, what makes this a truly remarkable visual document is that many of the immigrant boarders are holding up photographs of their own – some of which are clearly family portraits of loved ones back home. Again, historian Sarah Bassnett offers a penetrating reading of the photograph, observing that although Goss’s image served sociological and political purposes – illustrating overcrowding as part of a commissioned report– it contained within it a refusal to simply represent deplorable living conditions. The photos the men hold up both emphasize their displacement and their desire to be reunited with families. Goss has endowed them with no small degree of agency and depicted them as fully human and not simply as a social problem (2).

Other photographs from the 1913 project are also impressive. These range from outdoor shots of back yards that not only illustrate sanitation issues but are composed beautifully with fences and buildings providing striking leading lines, to more formal portraits of expressive nursing mothers at a municipally sponsored baby clinic. The city continued to call on Goss for other special ventures. These included an investigation into immigrant youth and schooling, a survey of housing stock in “problem” neighborhood, and when war mobilization began, documentation of military training and preparedness. Many of his photographs – along with those of Beales and Pearson — made their way into municipal reports and publications, though whether city officials understood them as more than illustrations or grasped their visual subtleties is open to question. However, what is abundantly clear from the sheer volume of photographic work in the Toronto Archives is that photography was a vital part of the workings of the city, serving to both document urban life and shape perceptions about it.

Although they later worked with assistants both in the field and in the darkroom, each of the photographers mentioned here were prolific in their municipal work. Indeed, much of their staggering output resulted from solo efforts on the streets and the lakefront. It is incredible that they found time to pursue photography for their own ends, with some of the very best work serving no larger political or administrative purpose. It is fitting, then, to close with Arthur Goss’s 1923 nighttime image of an automobile at a filling station on Dupont Street (figure eleven).

The station’s electric lamps and illuminated pump (recent developments) light the scene and allow for a sharp silhouette of a roadster, whose steering wheel and spoked tyres emerge in high relief. Light also bounces off the parallel lines of the trolley track laid atop cobblestone. All these elements stand out as emblems of the modern city, captured serenely in the dark by a master photographer quietly pursuing his craft.

(1) Bassnett’s 2016 book, Picturing Toronto, is a lavishly illustrated volume that develops these themes of photography and liberal reform at length. It also includes a wide ranging selection of Goss’s municipal work as well as his portraiture and landscape.

(2) See my earlier article on FRAMES on the birth of this urban documentary style.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rick Halpern is an historian and photographer based in Toronto. In recent years he has been writing about the history of visual culture, especially photography, and the way it has shaped our understanding of identity and place. His photographic practice focuses on three main themes: urban life, travel, and food.

Robert Wilson

August 21, 2021 at 23:12

Excellent article!

Susan Gans

August 22, 2021 at 04:58

Yes, an excellent article. This documentation reminded me of much work by photographers in New York City and across America in response to the Great Depression forward. These photos have been an invaluable resources for understanding urbanization and cultural history in America. Was not aware of the Municipal Photographs from Toronto and the impact of this work. Thanks!

Rob Leavitt

August 22, 2021 at 17:41

Fabulous article and historical view, thanks Rick! Love the range of photos here, a great tease that leaves me wanting many more.

Sandra Ch.

August 23, 2021 at 15:05

Absolutely amazing article!! I do admire the wonderful way to see, and read about History!! Thanks God for the existence of the photograph inventor, and all the historians who delight us with!!!

John C MacAlister

August 11, 2023 at 12:08

Thanks for the article: I lived in Toronto between 1978 and 1992 and this review prompted me to order a copy of Basnett’s book.