My last column exploring the heyday of American documentary photography in the Depression era raises an interesting question: what were the origins of the documentary tradition? While some might quibble as to precisely when the camera first was used to make a conscious record of social life, there is little doubt that at the turn of the last century, reformers began to harness photography – still a relatively new technology – to further their various causes. Two of the best known and most talented photographers to lend their skills to social reform were Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine.

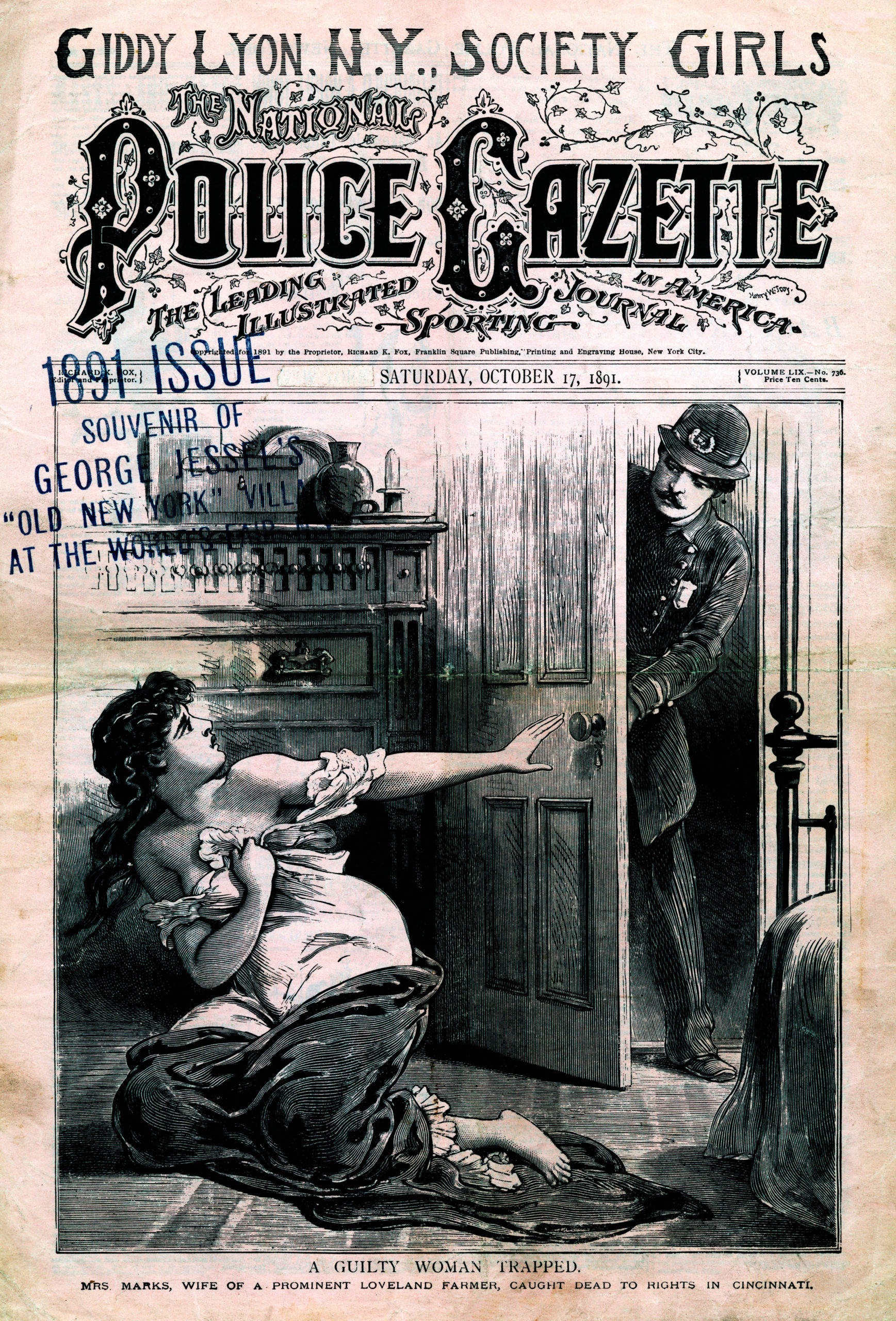

A Danish immigrant, Jacob Riis was a journalist who honed his photographic skills depicting children and delinquent teens on the streets of New York’s lower east side – the “street arabs,” waifs, orphans, gang members, newsies, and shoeshine boys who eked out an existence that both shocked and titillated the middle-class readers of the city’s middlebrow dailies for which Riis wrote. Indeed, Riis – either consciously or not – modelled his work on the sensational crime reporting that sold newspapers to a public hungry for scandal and a peek at the underside of urban life. Perhaps the best known of these early tabloids was the Police Gazette (see figure 1), published from 1847 until it was banned from using the US mail a century later.

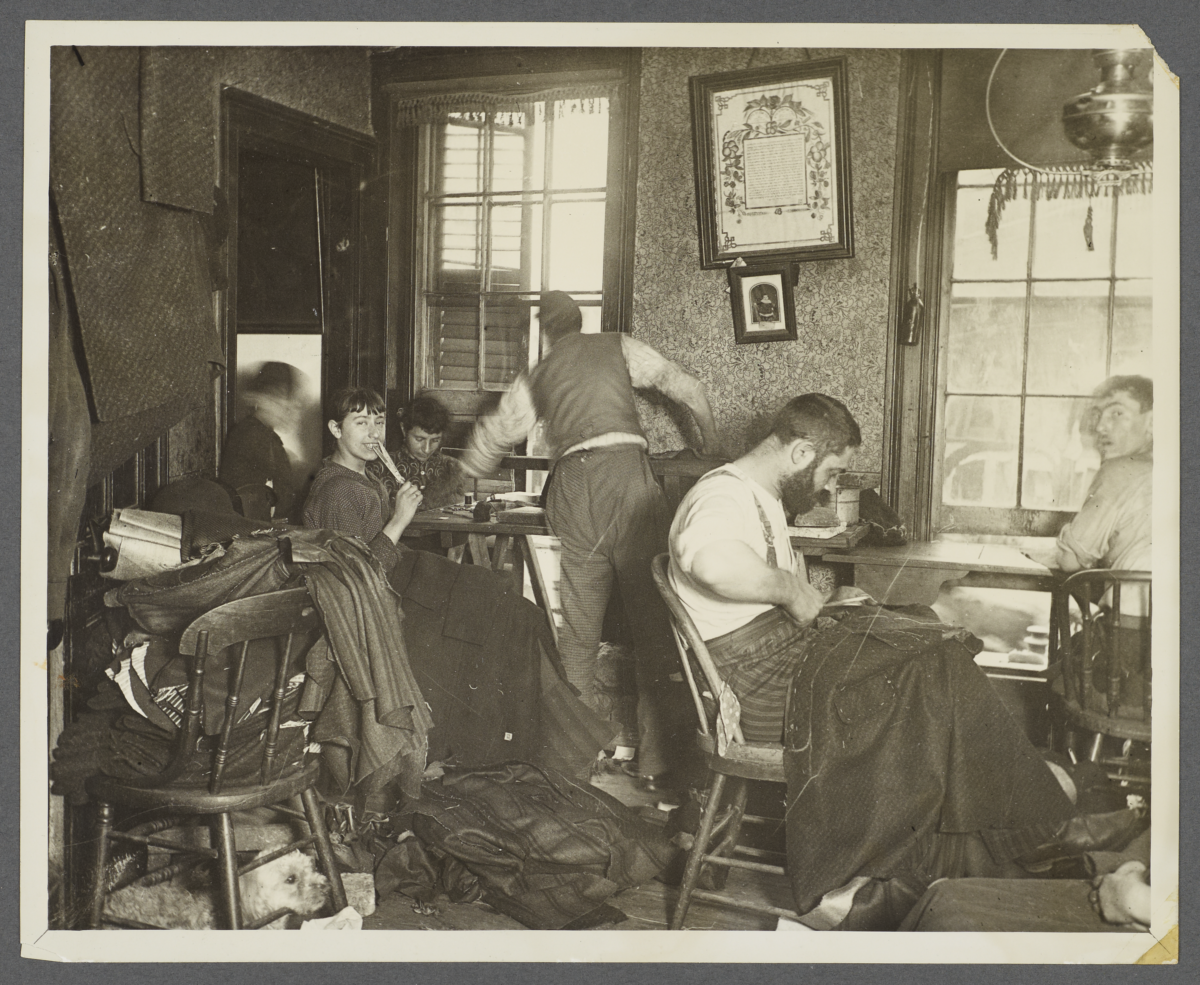

Riis took advantage of advances in technology, most notably the use of flash powder made from magnesium and potassium chlorate that could be crudely ignited at the same time an emulsion plate was exposed. This allowed him to capture images of slum life in dark interiors and shadowy alleyways, conveying scenes that respectable New Yorkers avoided (see figure 2). There was a sensational element to Riis’s work, captured in the New York Sun’s almost breathless 1888 description of his first published photographs: “Flashes from the slums: Pictures taken in dark places by the lighting process: Some of the results of a journey through the city with an instantaneous camera—The poor, the idle and the vicious.”

Yet Riis deserves to be known as more than a journalist out to excite and arouse concern for the poor. It can be said that he pioneered what we now term street photography, capturing the feel and texture of an urban canvas in an emotionally powerful and distinctive way in an era before rolled film and portable cameras. He also systematically photographed the sweatshops and work sites of late nineteenth century New York’s “putting out” system. His 1890 publication, How the Other Half Lives, included sections on “The Sweaters of Jew Town,” and “The Bohemians – Tenement House Cigar-making” that contain arresting images of work shot on location. These photographs have a poignancy and freshness that differentiate them from everything that came earlier. Despite the bulky equipment Riis lugged around, the best of his photos feel candid, as if the viewer has stepped unannounced into a Mulberry Street loft or Broome Street apartment. In one image of cigar rolling, a bearded husband and polka dot dress-wearing wife sit at an inclined board, intent on their work, while two boys, one preparing a tobacco leaf, stare directly at the camera in fascination. In another, six young necktie makers in a Division Street workshop are captured laboring away, but the facial expressions vary from curiosity to weariness. The refuse cluttered floor, print wallpaper, and long work aprons complicate the view.

The most arresting photographs that Riis shot serve both his didactic purpose and endure as landmarks of visual culture. His photograph of a twelve-year-old boy pulling threads from a garment (see figure 3) haunts the modern viewer – the seated child looks up from his work and directs his gaze at the photographer. His left eye appears bruised, and an odd cap sits jauntily on his head. Behind him five adults stare at the camera; one bespectacled man, hands on hip, has a half smile. The boss of this small operation? An immigrant on his way up on the backs of his landschaftsmen? We are not told. Another photograph depicts a Ludlow Street sweatshop (see figure 4). In the foreground a muscular cutter works his scissors around a pattern while, deeper into the frame, another man, in motion, is caught from behind, vested arms akimbo. To the right, a boy turns to glance over his shoulder at the camera while, on the left, to other figures (one blurred) focus on their work. Breaking the scene of hard labor, a girl off center smiles while touching a large pair of scissors to her nose.

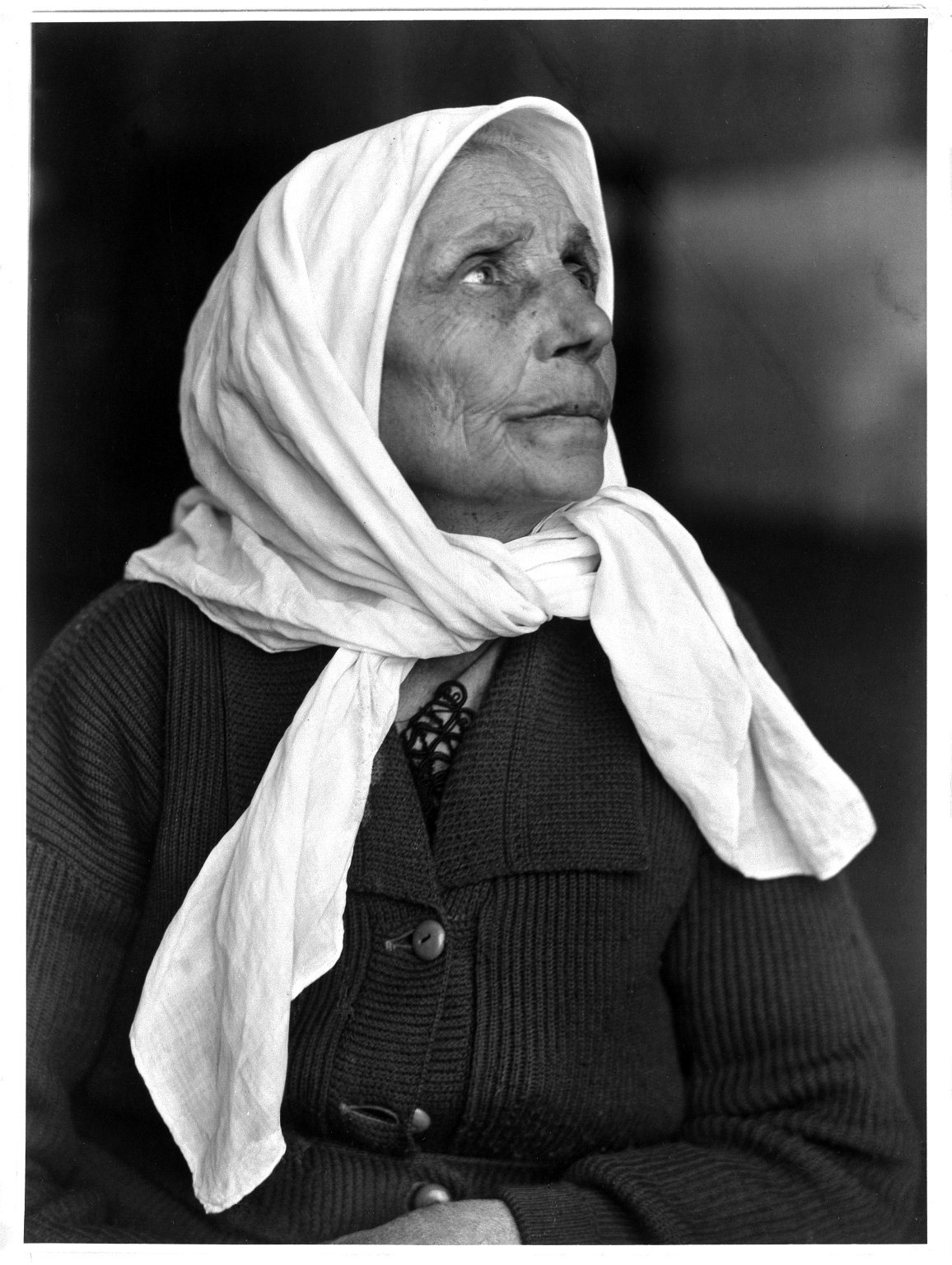

How the Other Half Lives marks the start of a long and powerful tradition of the social documentary in American culture. The plight of the most exploited and downtrodden workers often featured in the work of the photographers who followed Riis. Without doubt his most direct heir was Lewis Wickes Hine, a Wisconsin born reformer who refined the documentary camera work of the era and perfected its use as a social tool. A superbly accomplished technician, Hine’s first notable subject was immigrant America. In 1904 he executed a remarkable series of portraits of newly arrived European immigrants at Ellis Island, capturing a range of styles of dress, physiotypes, and facial features while avoiding the maudlin and picturesque. In contrast to the sensationalism that characterized Riis’s expedition into the slums, Hine’s portraits presented newcomers – to a dominant society increasingly restive and concerned about the wave of proletarian migration breaking on its shores – as dignified and self-respecting (see figure 5). In the years that followed, his turn to documenting industrial work was similarly motivated – here, in a sprawling body of work for which he is best known, Hine sought to convince the larger public to embrace working people and a vision of a reformed industrial capitalism.

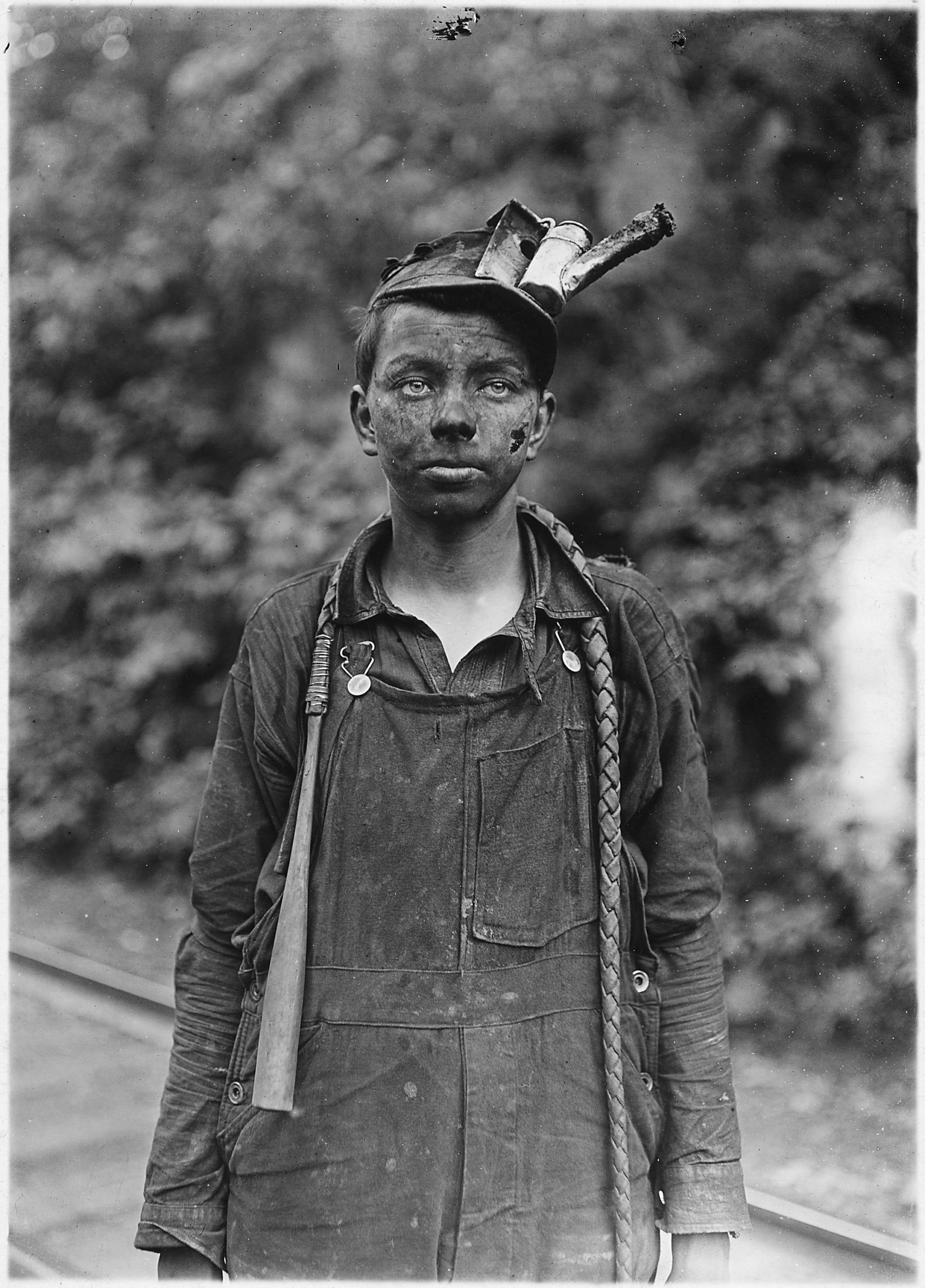

The documentary aesthetic Hine developed in the Ellis Island portraits carried over into the factory. Hine’s great cause, and new subject, was child labor, particularly in the anthracite coal fields and inside New England and southern textile mills. Many of his coal images are reminiscent of the immigrant portraits, especially when they focus on a lone young laborer, dignified in bearing though coal smudged, looking straight into the lens, outdoors in natural light, seemingly caught between childhood and adult status as a wage earner (see figure 6).

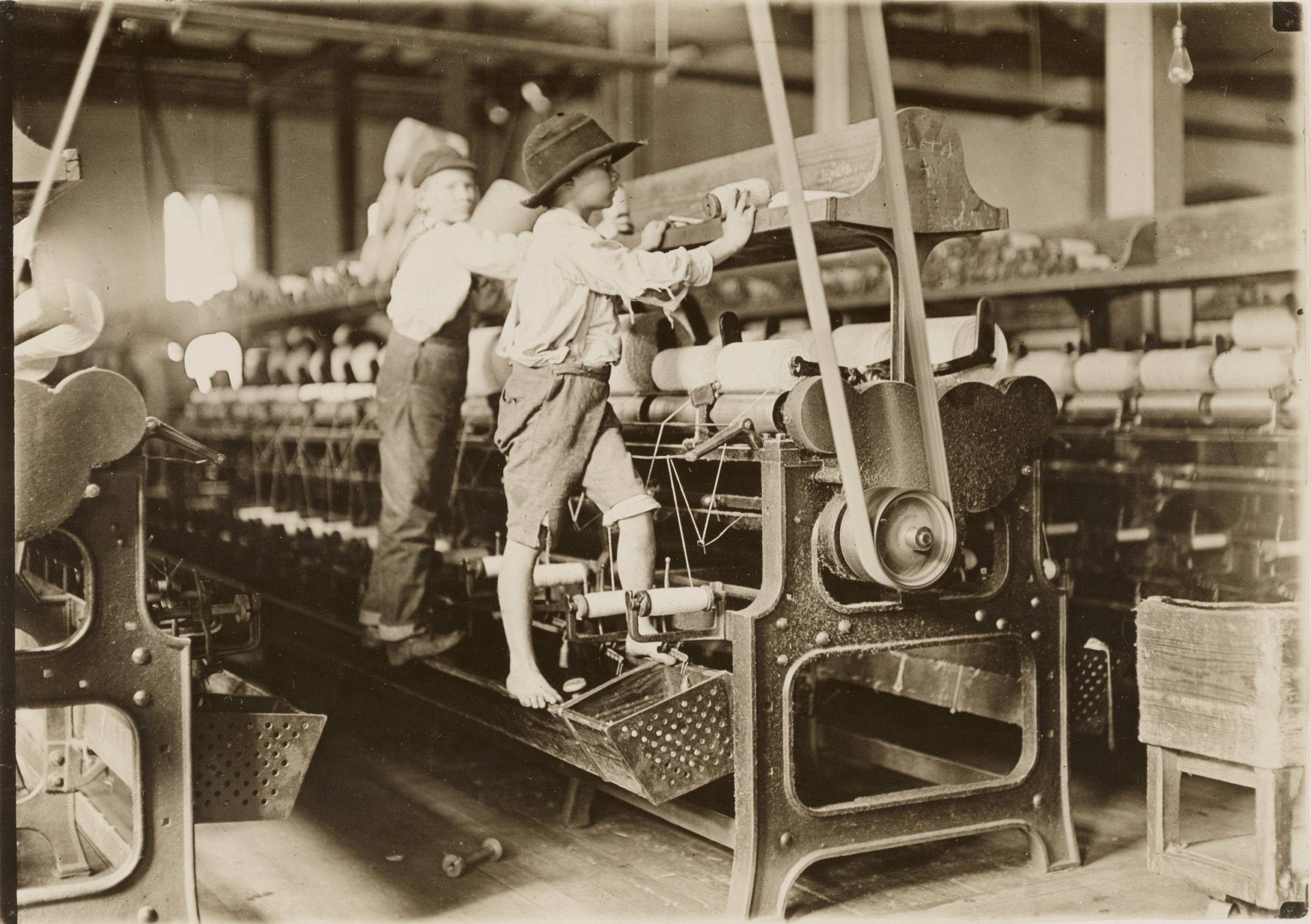

However, the other photographs, and the textile mill series in particular, are shaped by a very different sensibility. Tack sharp focus, precise depth of field, crisp detail, leading lines, and straightforward lighting mark a modern realism. In what may be Hine’s most famous single image from this period, “Sadie Pfeiffer, Cotton Mill Spinner,” (see figure 7) all these features are in play. The same holds for another well-known and oft-reproduced image, “Young Doffers” (see figure 8). In both photographs young children are at work, dwarfed by heavy machinery, and in danger of being caught in the open and moving pieces of the mill. The emotional impact is heightened in the second photo by child in the foreground who is barefoot, though he has mounted the spinning machine to reach the bobbins, wears short trousers and sports a hat that is several sizes too large for his small head.

As a tool for reform Hine’s child labor photographs received wide circulation in progressive journals such as The Survey, Charities and the Commons, Everybody’s Magazine, and other periodicals. They were effective, all the more so because Hine often presented these pictures in the form of “stories,” linking them with title, captions, and interpretive text and accentuating their modernism by using new artistic techniques such as photomontage. A reform minded public also became aware of his work through his sponsoring agency, the National Child Labor Committee, which produced flyers and posters, took out advertisements, and mounted travelling exhibitions, all of which featured Hines’ work. Yet, despite his technical brilliance as a photographer, and his marked ability to achieve a visual rapport with many his young subjects, Hines’ body of photographic work from this period – like Riis before him – denied workers agency and, instead, treated them as objects to be put to programmatic use in a campaign for protective legislation and regulation. The sweatshop workers captured by Riis and the child mill hands depicted by Hines are presented as victims in need of rescue.

In the 1920s Hine turned away from what he called “publicity and moral stuff” and the photographic documentation of social ills to corporate public relations, hiring himself out to companies such as National Cash Register and Western Electric. There, his work, while still striking, served to promote a harmonious vison of industrial relations, part of a larger move to promote welfare capitalism as an alternative to the sort of naked class conflict that characterized the turn of the century. Not surprisingly, Hines’ detour into corporate paternalism meant that in the 1930s, when the twin phenomena of the Great Depression and the emergence of a militant workers’ movement gave photographers interested in the working class a surfeit of material to shoot, Hines was on the sidelines and relatively unknown to a rising generation of documentarians.

Corporate photography forms an important strand in the history of the medium. Many businesses used photography in the early twentieth century not simply to promote their products but to document production processes, to monitor their employees, and to rationalize complex operations. But this is the topic of another, future, column.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rick Halpern is an historian and photographer based in Toronto. In recent years he has been writing about the history of visual culture, especially photography, and the way it has shaped our understanding of identity and place. His photographic practice focuses on three main themes: urban life, travel, and food.

Michael Todd

March 21, 2021 at 21:12

Wonderful article! It’s interesting that in the 1880’s facsimile reproductions techniques were not very good, resulting in Riis’s work not being recognized until some of his best work was posthumously published in U.S. Camera 1948.

Bernard Mitchell

March 26, 2021 at 17:33

Thank you Rick from Wales, great moving images of children working etc. Memorable. Bernard