Now widely regarded as one of the pioneers of documentary photography, the Frenchman Eugène Atgetlanguished in obscurity for most of his life, dying in poverty in 1927 with most of his work depicting turn-of-the-century Paris winding up in the possession of an indifferent acquaintance. Only the timely intervention of Berenice Abbot, at that time an unknown who had just begun to dabble in photography, saved Atget’s work for posterity. Abbott, of course, went on to become one of the twentieth century’s great photographers, best known for her images of New York City in the 1930s, but at the time her path crossed with that of Atget she barely was scraping by as a studio assistant to the artist Man Ray and had yet to find her own direction. Although she knew Atget only briefly before his death, Abbott managed to secure his collection of prints and thousands of negatives, bringing them to the United States in 1929 and tirelessly devoting the next few years to promoting him. Yet, more than simply facilitating the growing public appreciation of the older man, Abbott was profoundly influenced by Atget, who in many ways gave shape and purpose to her early photographic career.

Interestingly, Atget never really thought of himself as an artist or even a photographer. When he began taking pictures of Paris in the 1890s, he called his photographs “documents” and regarded himself as their “author-producer.” It was with this sensibility that he methodically wandered the avenues and back alleys of the city recording both architecture and street life. Atget’s documentary work falls into two broad categories, both of which anticipate the street photography of our own time. First, there are his images of the streets themselves, often empty laneways or bustling squares (see Figures 1 and 2).

Second, Atget excelled at candidly capturing working people going about their business: shopkeepers, artisans, day laborers, or even prostitutes (see Figure 3). In both cases his composition is always near perfect – years later Abbott commented that one of the more important things she learned from studying Atget’s photographs was where to position the camera and frequently spent hours determining the optimal spot for her own work, even after she started using variable length lenses.

Perhaps more important than technique to Abbott was Atget’s vision as an artist devoted to working the streets of the city. Rather than seek out aesthetically pleasing views to shoot, Atget photographed practically everything about him. “He saw abstractly,” Abbott wrote, and “succeeded in making us feel what he saw.” From Atget, Abbott learned that the street could have a mood or a personality, and that the job of a talented photographer was to capture that character on film and to do so in ways that evoked wonderment or surprise. It was with this purpose in mind that she evocatively once called Atget the “Balzac of the camera.”

Upon her return to New York, Abbott set out to emulate Atget’s approach. Basing herself in Greenwich Village, she methodically moved across Manhattan, scouting out locations and experimenting with the light at different times of day with a small camera before returning with her bulky 8 x 10 view camera to make the final image. This was a dramatic departure from the studio portraiture she had pursued in Paris, and the early results were both striking visually and clearly an homage to Atget. Of course, the differences in the built environment between New York and Paris were profound. The quaint laneways of Paris might find some faint echo in the back alleys of Little Italy or Chinatown (both of which Abbott shot) (1), but soon she came to focus her attention on the grandeur of New York’s skyscrapers and long avenues. Figure 4, shot in the Financial District, could not be mistaken for any other city in the world.

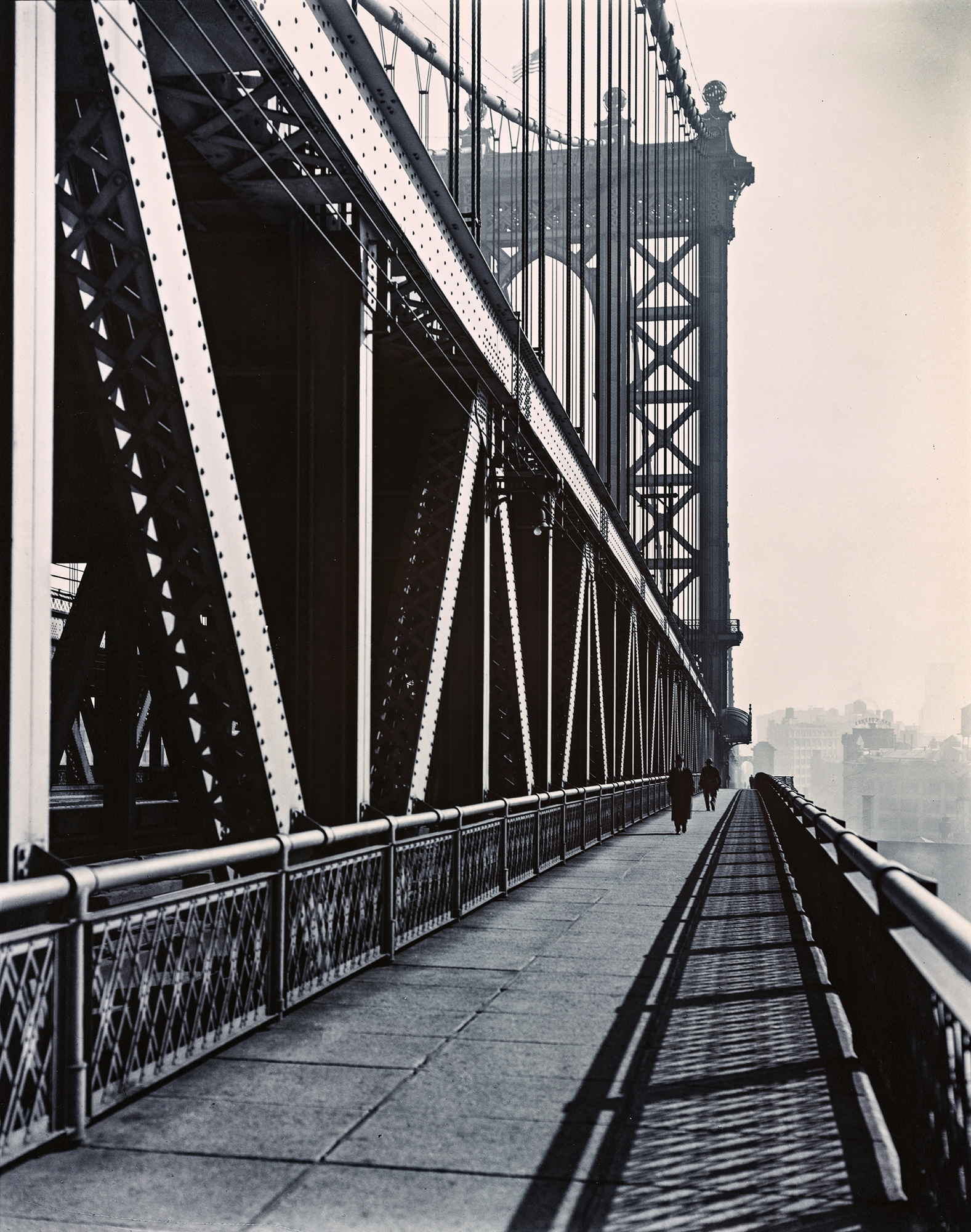

New York in the 1930s was undergoing a dramatic transformation. Old neighborhoods with single family housing were disappearing and construction was everywhere. New bridges linked Manhattan to the other boroughs; rail stations received facelifts and emerged as cathedrals of light; and iconic skyscrapers built with steel, poured concrete, and glass began to give the city its iconic skyline. Abbott captured it all. (2) Some of her best known photographs are of the George Washington bridge off Riverside Drive, then under construction, linking the city to New Jersey and the Manhattan Bridge closer to her home in lower Manhattan connecting to Brooklyn (see Figure 5).

The Manhattan Bridge photograph contains several elements that came to characterize Abbott’s New York City work: long leading lines, geometric patterns, and brilliant use of light and shadow. Many of her shots of the city’s avenues, often taken from the upper floors of a tall building, possess these traits as well (3), but they truly come to the fore in her multiple photos of the city’s elevated subway lines that then ran up both the east and west sides of Manhattan. Figure 6, below, is but one example of this sort of image. As the critic Julia van Haaften put it we see Abbott giving free rein to a formal modernist vocabulary in these sorts of photographs, using the “Vertikal-Tendenz” of angle views and skewed perspectives.

Abbott was keenly aware of the historical conjuncture of her New York project. Although still in the grip of the Great Depression, New York was managing to forge ahead and become the urban metropolis most closely associated with architectural and cultural modernism. Old and new lay side by side, often in a state of tension with each other. Contrasting the city to Atget’s Paris, Abbott declared that his photographic work looked sedately back to the nineteenth century and hers forward into the twentieth. “I live in a world where the basic facts are contradictions, conflict, insecurity,” she wrote, an apt summary of both her time and her creative output.

This dynamic view was concretized at the end of the decade when Abbott published Changing New York, the culmination of her documentary project published under the auspices of the Federal Art Project, which had employed her to complete the work she began ten years earlier.

Atget was never far from Abbott’s mind in the 1930s. She arranged for some small exhibitions of his work and oversaw a book length project, Atget: Photographe de Paris. Interestingly, she failed entirely to enlist the support of the doyen of American photography, Alfred Steiglitz, who dismissively declined to show Atget’s prints at his uptown gallery.

Although Abbott’s embrace of photographic modernism, and her ability to push it forward onto new terrain, distanced her as a visual artist from Atget, his influence on her practice remained powerful. This is seen most vividly in her photographs of storefronts and people, where the realist sensibility of the older man infused her images. These affinities are especially visible in her shots that eschew long perspectives and opt instead for more straightforward documentation (see Figure 7) or when she used contrasting light and shadow to illuminate workers rather than buildings (Figure 8).

Berenice Abbott’s 1929 decision to return to New York from Paris had monumental consequences for the history of photography. Not only did she carry with her a streamer trunk filled with Eugène Atget’s most important work, she introduced him to a new and wider audience (and continued to promote him as a master of the craft for the rest of her life). She used her location in New York to pioneer a new kind of urban modernism, one that drew inspiration from Atget’s patient but dogged documentation of Paris even as she moved into artistic realms that the master never could have envisioned. Abbott’s own detailed work on New York captured the metropolis in a signal moment of its transformation. Never losing sight of the humanism of the city, she tacked back and forth between the distinctive geometric forms that defined the city and the people who inhabited it. Although she later moved on to explore other fields of photographic endeavor – most notably science and optics – her prodigious output in the 1930s continues to inform the way we think about the visual culture of the twentieth century city. At a time when photography was struggling to move away from the pictorial tradition, Abbott showed how a documentary practice could rise above the journalistic and produce fine art.

(1) Some of Abbott’s very first New York photographs were shot in Chinatown, shown here in a series made with her smaller hand held camera on one of her scouting expeditions.

(2) Abbott’s photographs of both Pennsylvania Station and Grand Central Station are among the best she produced in this period.

(3) See, for instance, “Seventh Avenue looking south from 35th Street,” 1935.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rick Halpern is an historian and photographer based in Toronto. In recent years he has been writing about the history of visual culture, especially photography, and the way it has shaped our understanding of identity and place. His photographic practice focuses on three main themes: urban life, travel, and food.

Desiree+Day

January 17, 2022 at 16:01

Wonderful article on Atget and Abbott. Thanks Rick for such an informative piece.

Cynthia+Gladis

January 22, 2022 at 15:43

Excellent article about two of my favorites. Thank you!

Frank Styburski

January 26, 2022 at 18:46

I like Abbott’s work for the use of space, geometry, and patterns that inhabit her pictures. All conceptual expressions that seem appropriate for an imagist who was attracted to the forward looking mindset of the Twentieth Century.

It was stroke of luck that Abbott saw the merit in Atget’s work, and had the savvy to successfully be his advocate. My own experience tells me that nobody cares about our photographs as much as we do, (present company excepted). I have to wonder how many invisible photographers die without their work ever achieving the the recognition it deserves. Worse yet, to be summarily dismissed, and see it destroyed, -simply because nobody cared.

The work of Vivian Maier comes to mind. What a tragedy it would have been to have never seen it. Again it was a stroke of luck that someone with marketing know-how acquired it, recognized the value of her work, and understood how to create an exploitable mystique. Otherwise it would have been lost, not noticed, and not missed.

Thanks for the article, Rick. While I’m familiar with the work of Atget and Abbott, I wasn’t aware of their connection to each other. I have a deeper respect for Abbott’s character after reading it.