The decade that ended the nineteenth century was a formative period in the history of US empire. Two crucial developments, occurring almost simultaneously, changed the way that Americans thought about their country, its place in the world, and the racialized nature of its citizens and subjects. The first of these was the “closing” of the frontier, the 1893 announcement by the Bureau of the Census that in the West there no longer were tracts of land without settlers. The second was the sudden acquisition of a far-flung overseas empire in the wake of the Spanish-American War. Photography played an important but underappreciated role in documenting and interpreting both these events.

This article will unfold in two distinct parts. The first, presented below, focuses on the way photographers made sense of native peoples in the western United States at a time of rapid change in the region, depicting them as a “vanishing race” whose disappearance, while lamentable, left the land and its resources open for development The second, which will appear in my next column, explores the multiple uses to which photography was put in America’s new overseas colonial project, acquainting Americans with their new subjects and powerfully contributing to the categorization of these people in a racial hierarchy that was very different than the black-white binary to which Americans were accustomed.

It is one of the more remarkable photographs of the era (see the featured image above): a veritable mountain of bison skulls dwarfs the human figures in the foreground and atop the grisly pile of bones. Shot by an unknown photographer in 1870, the image bears grim witness to the final stage of the decades long campaign to break the fierce resistance of the native peoples on the Plains. Using the twin technologies of the railroad and automatic weapons, a combination of white settlers and the military undermined traditional nomadic native ways of life by destroying the great herds that provided food supply, clothing, and cultural grounding to thousands of people. “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone,” declared the showman William “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

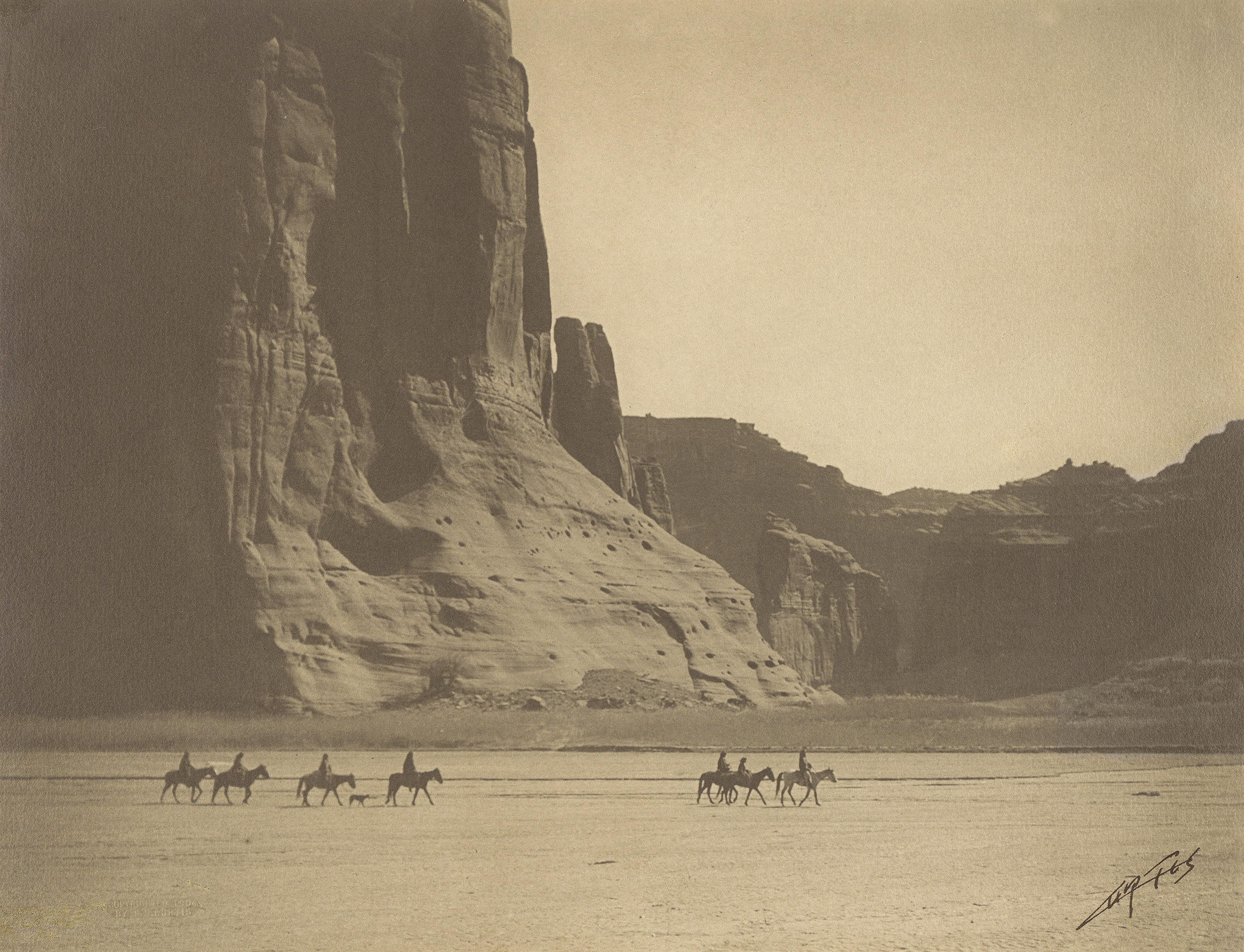

Yet this photograph is an outlier. Aside from several images of battlefield monuments, such as the site of George Armstrong Custer’s infamous “last stand” at the Little Bighorn in Montana, the vast trove of photographs documenting this stage of western history are mute when it comes to conflict with native peoples and the means deployed to subjugate them. This is ironic, for some of the finest photographers of the day documented both the natural beauty of the West and the indigenous peoples who inhabited these lands. Yet they did so in ways that, while often sympathetic to the native cultures being eroded, obscured the reality of their struggles for survival. Instead, the best photographs of native life are steeped in an ideology that celebrates in almost elegiac fashion the passing of a noble civilization. This is a message clearly conveyed in the work of the most renowned of these photographers, Edward S. Curtis, who spent several decades documenting the American Indian, making more than two thousand prints and, with the assistance of wealthy benefactors, publishing several folio volumes of work. Figure two below, entitled “The Vanishing Race,” captures this well as four barely distinct horsemen ride away from the camera, following a trail that disappears into a blurred frame with a bulking rock outcrop as a looming backdrop.

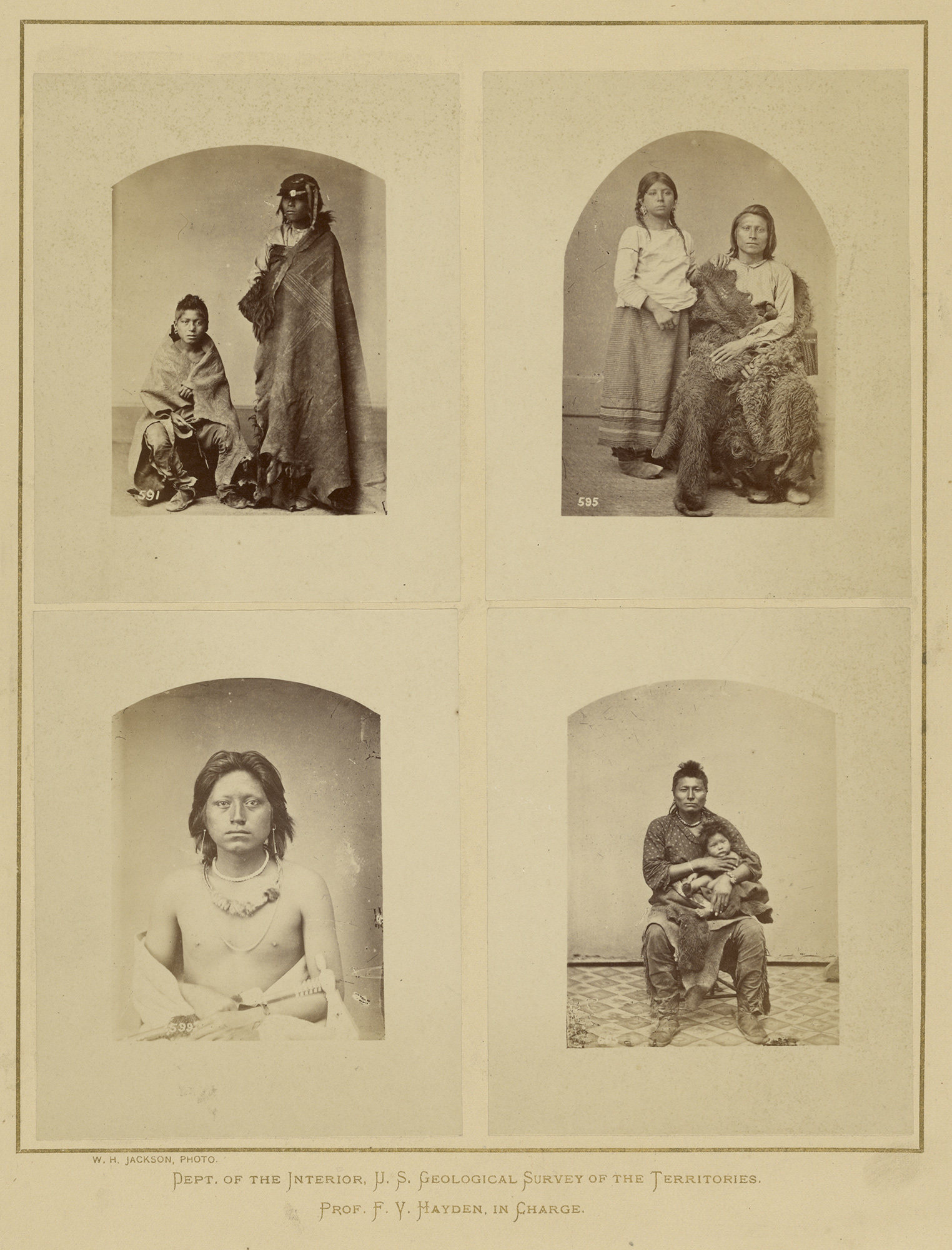

Curtis’s photographic work came near the end of a long documentary project, one that began just after the Civil War under the auspices of the Department of the Interior when it commenced a comprehensive survey of western territories. Primarily interested in documenting landscapes and geological formations, these expeditions attracted some of the most talented photographers of the day, several of whom used the opportunity to travel and shoot at government expense to pursue their own personal interest in native peoples. A prime example of this is William Henry Jackson, who got his start as a commercial portrait photographer, became bored with the business, and in 1870 won a commission to help document the West. Using an albumen print process that allowed for extremely sharp images, Jackson produced superb landscape work, but it is his photographs of tribal life and material culture that concern us here. His background as a portraitist clearly shaped this part of his output, as figure three below demonstrates. Here, carefully posed images of Pawnee men and women in traditional dress serve as a valuable record, even if they are studio shots that remove the subjects from their own dwellings and surrounds.

Jackson later found work with the Bureau of American Ethnology, a group of anthropologists at the United States National Museum (later the Smithsonian Institution) responsible for some of the most important collecting of native artifacts and photographs. Here, he became the first to shoot the prehistoric Native American dwellings in Mesa Verde, Colorado and the Pueblo and Hopi peoples of the southwest. He eventually settled in Denver, where he worked as a commercial landscape photographer and published his photographs as postcards.

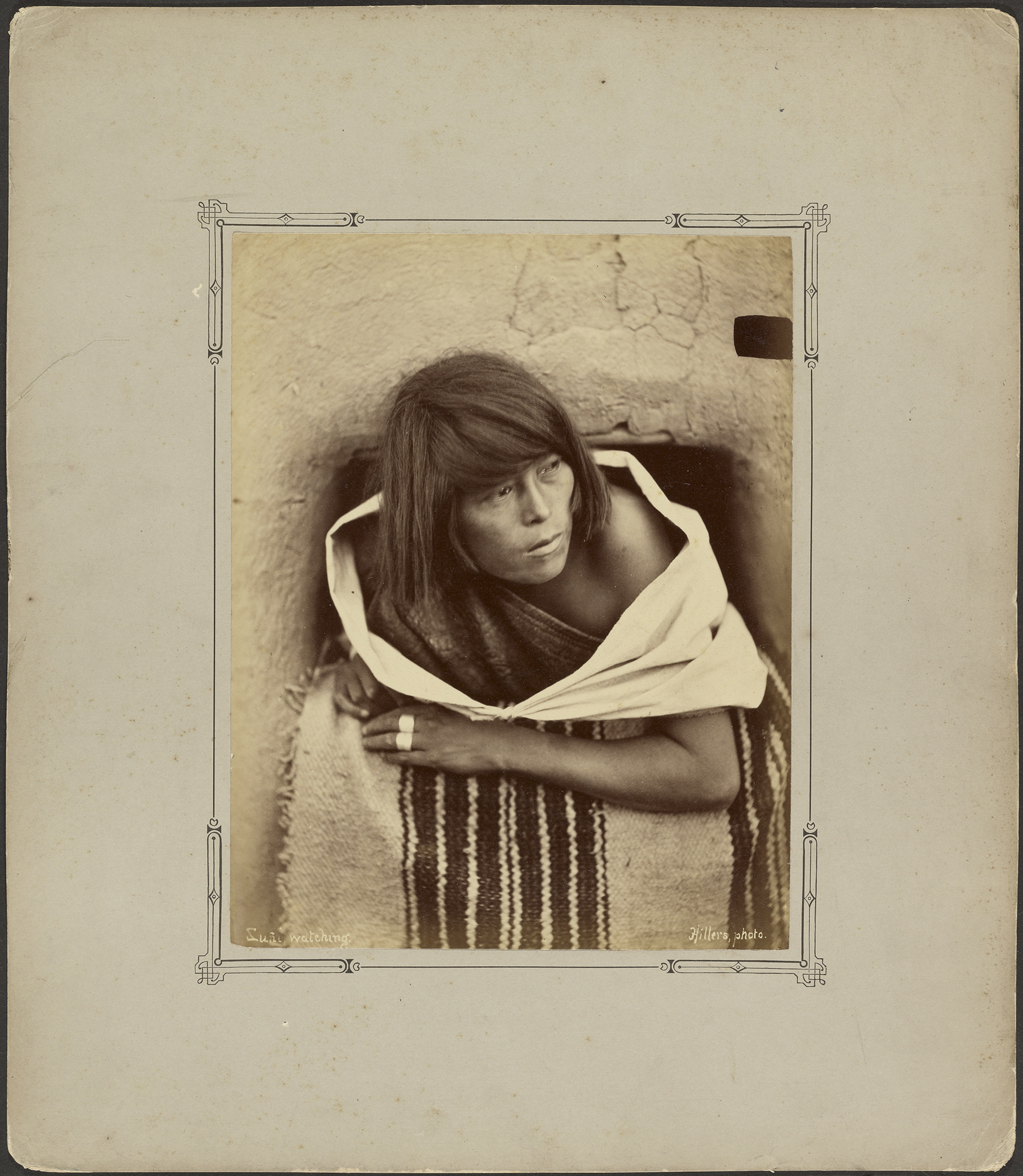

A more creative government photographer whose career paralleled Jackson’s was John K. Hilliers, who spent his entire adult life in federal employ. Originally hired as a boatman on John Wesley Powell’s renowned survey of the Colorado River, Hilliers became increasingly interested in the work of the team’s photographer, began acting as his assistant, and by 1872 had become the expedition photographer. As this picture of a Zuni woman (figure 4) amply demonstrates, Hilliers became an even more accomplished portrait photographer than Jackson, partly because he shot in natural settings, but also because of his willingness to depart from formal norms and experiment with pose, lighting, and appropriate props.

As wonderful as these portraits are to the modern eye, Jackson and Hillier’s ethnographic work cannot fully be separated from their landscape photographs. Indeed, what is notable about the corpus of landscape images produced by both the Department of the Interior and the National Museum is the total lack of people in the frame of the vast majority of photographs. Their documentary and artistic value aside, the message conveyed is that the lands of the West are empty, waiting for enjoyment, settlement, and economic development. The photographs of Native American life, many made at the peak moment of armed conflict with US authorities, suggest a subdued and conquered people who pose little threat to westward expansion.

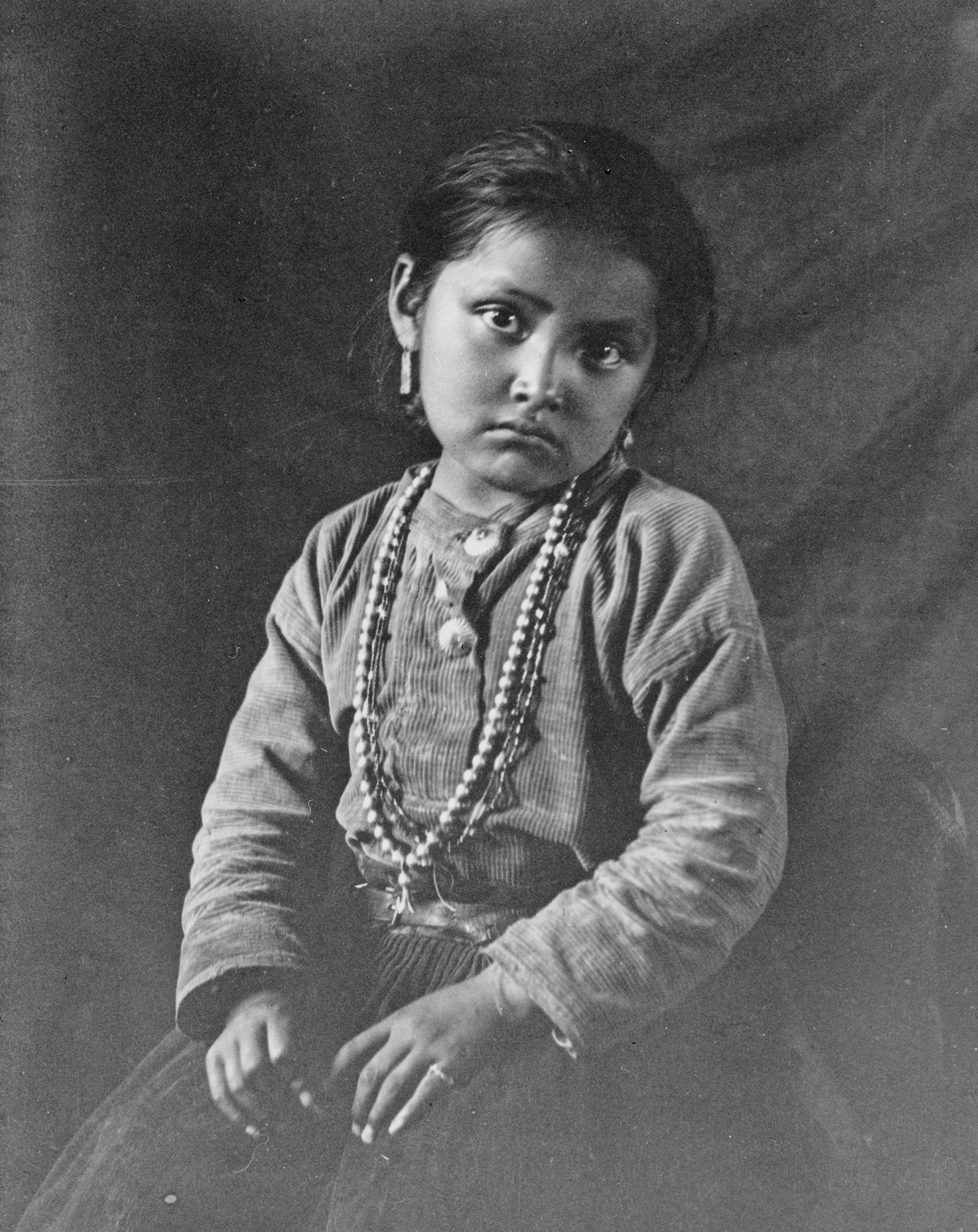

This dichotomy, or tension, between a somewhat romantic view of noble native peoples and a disappearing or depopulated West is also found in the work of independent photographers who made lifelong projects of documenting native cultures. One of the most accomplished of these photographers was Carl E. Moon, a Midwesterner who relocated to the southwest and used both oil paint and the camera to depict the native peoples of that region. Technically proficient, having studied photography in school, many of Moon’s photographs are sentimental to the point of being maudlin, such as his relatively well-known, “Little Maid of the Desert” (figure 5 below) or a picture entitled “Last of His People” depicting a lone, dejected looking male figure clothed in only moccasins and a barely visible strip of a loincloth. (1) Titles such as “Primitive America” or “Lost Village” convey a world just beyond a veil, receding in history and memory. (2) Yet many of Moon’s photographs rise above this sentimentality and deserve recognition as masterful pieces of art. His oft-reproduced sepia portrait of a Navajo youth or his breathtaking photograph depicting an Acoma Pueblo woman sitting alongside a natural water well with a patterned painted jar fall into this category. (3)

Yet of all the photographers of the West, it was Edward S. Curtis – certainly it is his work that received the widest contemporary circulation. To this day, he continues to enjoy a high degree of popularity. Curtis is a challenging figure to understand. His photographs are remarkable in both composition and technical skill, and the range of his oeuvre is extensive in its geographic coverage, ranging from the Great Plains to the Pacific Northwest on both sides of the Canadian border. Yet, Curtis, we now know, manipulated his subjects, often carrying costumes and jewelry from one region and directing people in another area to wear them or to pose in ways that were unnatural and out of place. These interventions render his work dubious as accurate documentary evidence and complicates its interpretation while, at the same time, often heightening its creative impact.

Curtis’s 1904 photograph, “Canyon de Chelly,” and “The Eclipse” shot a decade later are cases in point (see figures 6 and 7 below). “Canyon de Chelly” may be his best-known image, it has been reproduced countless times and adorns the cover of two collections of his work. It is a powerful shot, capturing not just the natural beauty of the canyon but seven riders and a dog as they move across the barren landscape. The photo was posed and, apparently, Curtis had the horsemen ride several times, spaced at different intervals, in front of his lens. Moreover, this image and hundreds of others that Curtis produced, feature native peoples in vast expanses of land, suggesting a freedom to roam or even ownership of these open spaces. Yet these photographs were made at a time when plains and southwestern tribes had lost title to their lands and were increasingly confined to reservations.

“The Eclipse” is even more problematic. Again, we know that Curtis orchestrated the scene, even lighting the smoldering fire himself. The Pacific Northwest coast Kwakiutl tribe, shown here, were noted for their elaborate ceremonies, often involving dance, but it is not clear that the bundles carried aloft by the dancers are part of this ritual or an element added in Curtis’s choreography. Likewise, the reed cloaks visible on the figures to the right of the frame may have been carried inland by Curtis and his team.

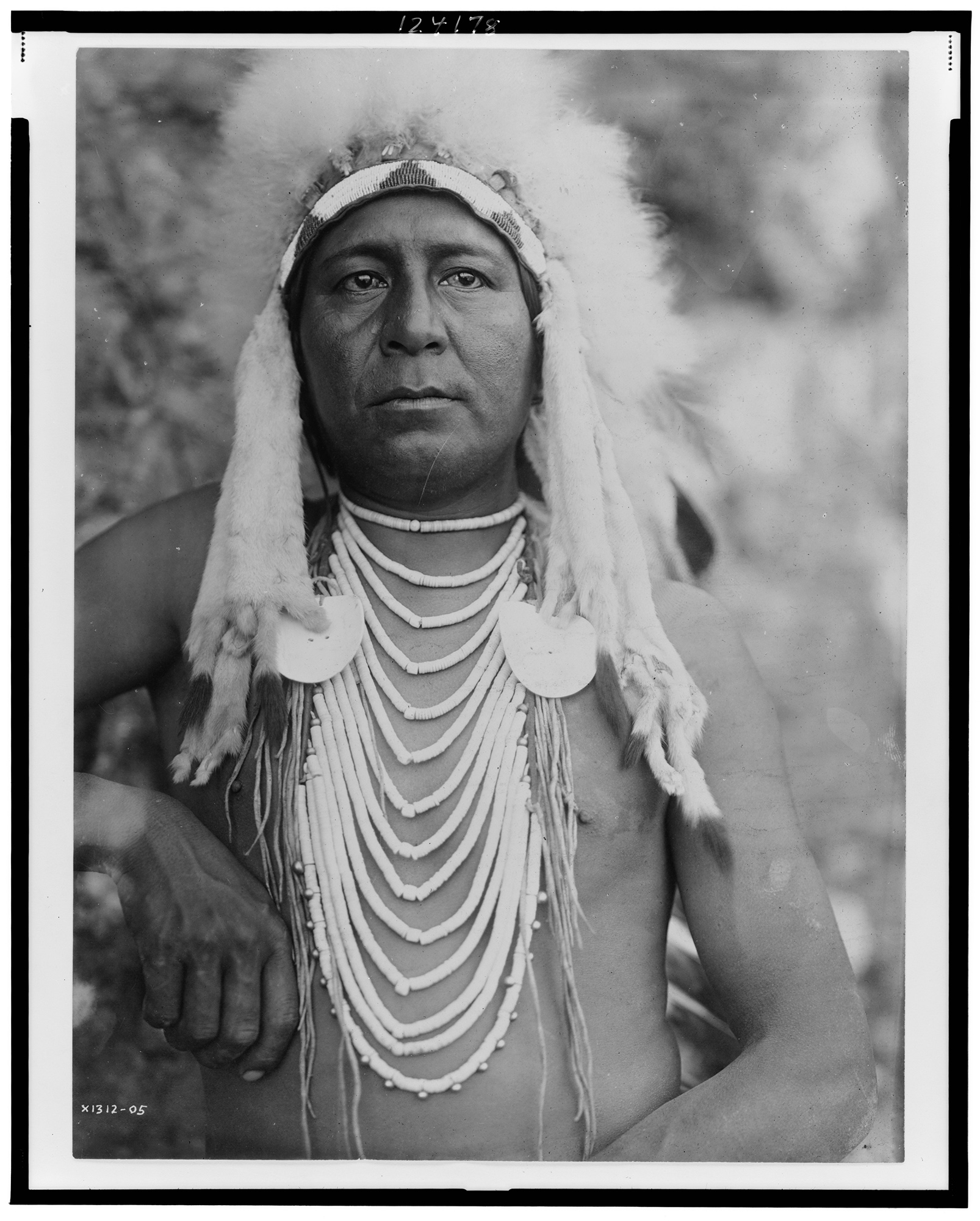

Throughout his endeavours in the West, Edward Curtis relied on the assistance of Alexander B. Upshaw, the son of an Apsaroke chief, who served at Curtis’s right hand man for three decades. A 1907 photograph of Upshaw provides additional, and somewhat disturbing, evidence of Curtis’s penchant for manipulation. Here, he photographed Upshaw adorned in traditional tribal gear, bare-chested, and wearing a feathered headdress (figure 8 below). The portrait is striking, but it is also exemplary of the tweaking in which Curtis regularly indulged to capture powerful images. Upshaw, although descended from the Apsaroke, chose not to live as a native. Educated at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, he was an accomplished photographer in his own right, an explorer, interpreter, and writer. On the job with Curtis, he dressed in western clothes, most likely dungarees, and wore his short hair neatly parted. As the critic Zamoon Shamir has noted, the photograph is an illustration of romance over reality, of genre conventions and racial typology over genuine portraiture.

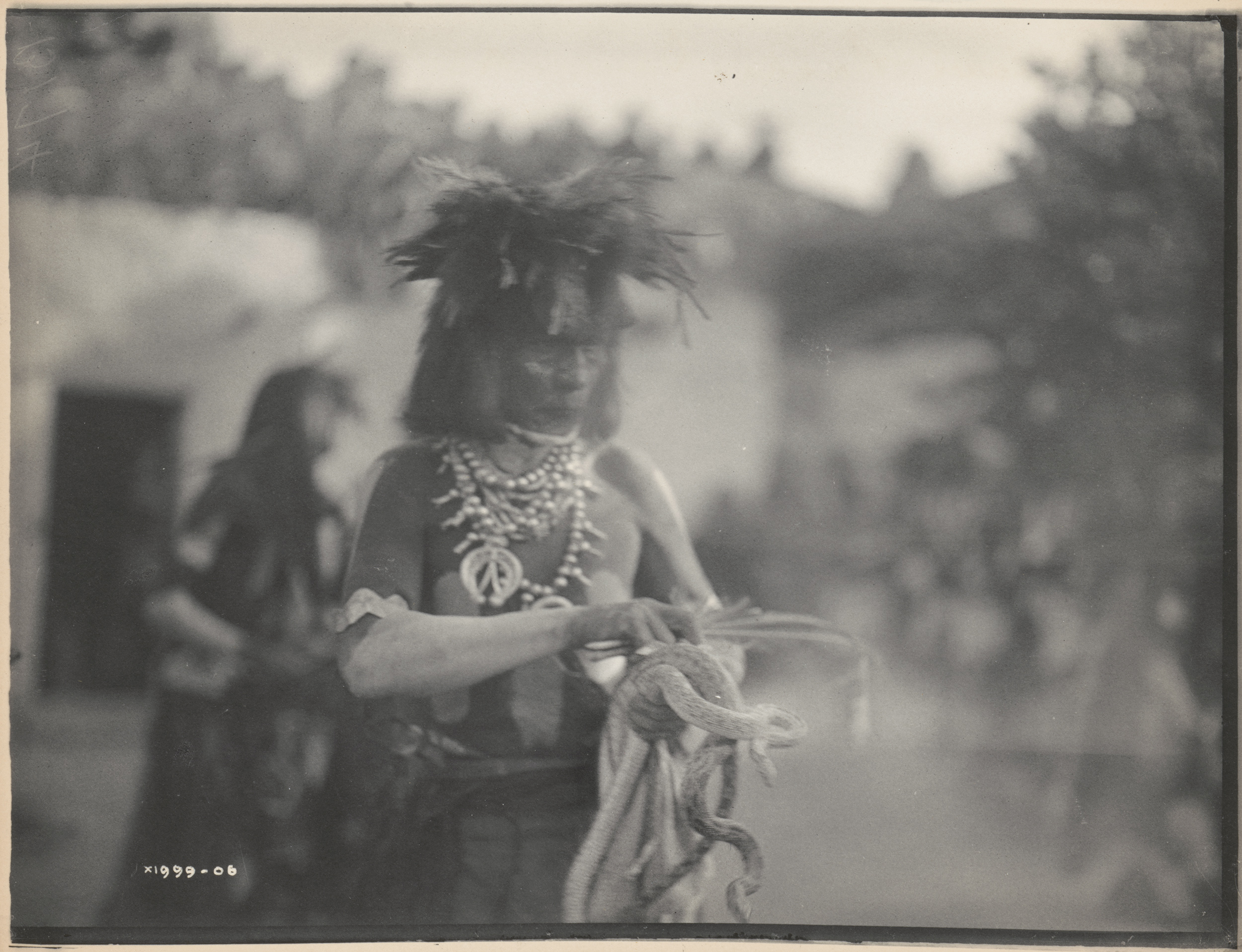

This is not to suggest that Curtis’s work as a photographer of the West is without merit, or that as a documenter of native culture he needs to be dismissed as a deceptive charlatan. Rather, we need to recognize that he pursued his project with passion and with noted sympathy for his subjects, even if the images that we encounter a century later must be understood as constructions of the past. Moreover, important parts of Curtis’s output are valuable as ethnographic evidence of tribal cultures long vanished, especially when we can contextualize them with other historical evidence. A good example of this is the series he created in 1905 and 1906 of the Hopi Snake Dance, a religious practice central to the Snake and Antelope clans, and at the time Curtis was active in the southwest the practice was banned by white authorities and had to be performed in secret. Some of these photographs are not especially good from a technical or artistic standpoint but are illustrative of the important ritual. Figure 9, below, for instance, is an extremely rare image of a high priest, with writhing serpents in hand. (4)

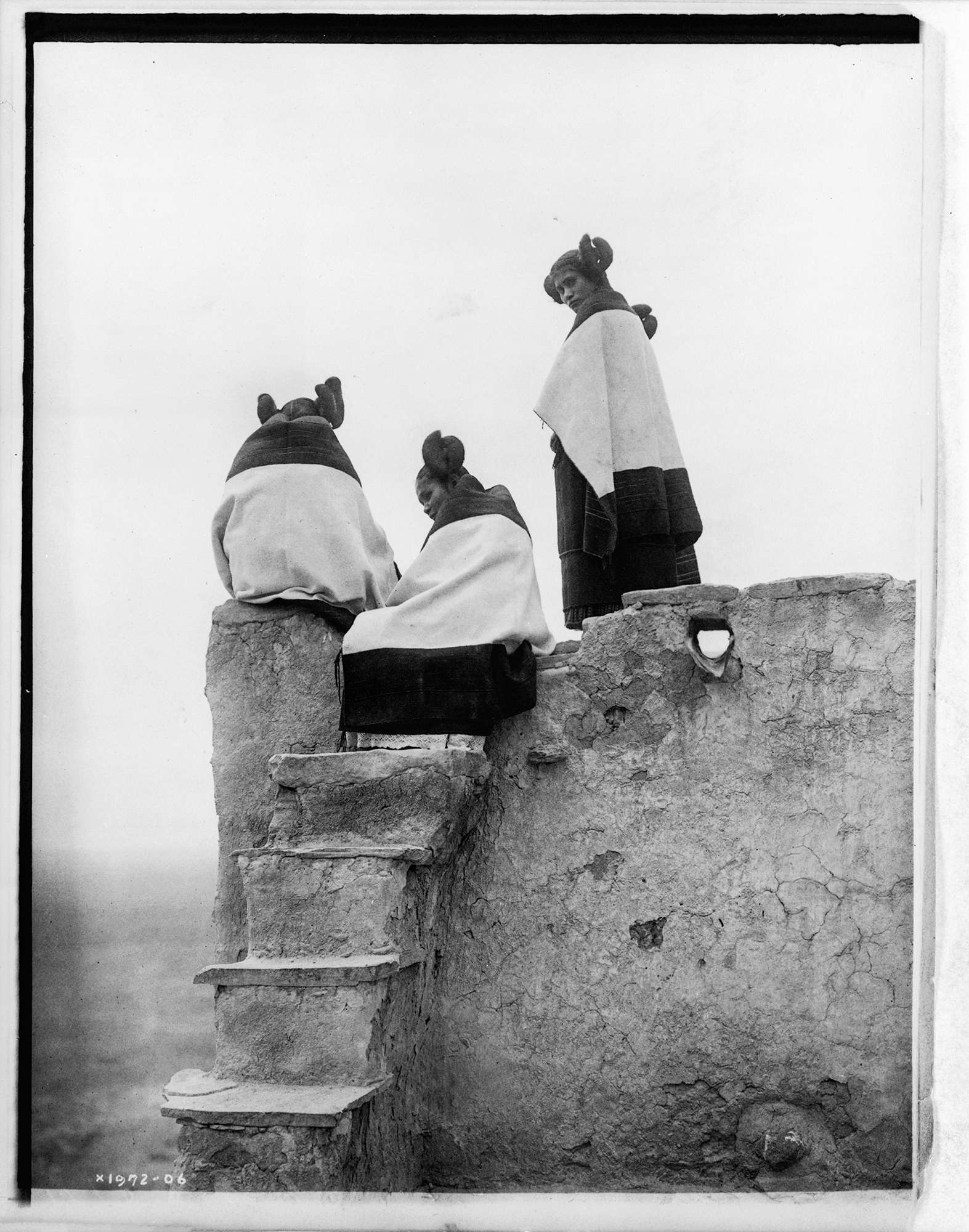

A companion series, shot on the same field trip as the Snake Dance photographs, captures various spectators, including young women with traditional dress and hair styles, sitting high on the adobe walls watching the dancers below. Though of limited anthropological value, these photographs are among Curtis’s very best from an artistic point of view, with extraordinary framing and composition (figure 10 below).

Photographers such as Jackson, Hilliers, Moon, and Curtis were but a few of those documenting the American West as native culture came under relentless assault from a modernizing nation that was intent on squeezing the indigenous peoples of the Plains and the Southwest to the very margins of a national narrative of progress. That Native Americans were not forced out of the frame altogether owes something to the photographic work of these men, even if their images are challenging to interpret and place alongside a more inclusive social history of expansion. Some contemporary viewers of these images might not be entirely comfortable seeing these events in the American West as chapters in the history of settler colonialism, but they should pause, at least for a moment, and consider this angle. Certainly, developments overseas fit more neatly into an imperial analysis – and this is what we will take up in the next installment of this column.

(1) Carl Moon, “Last of His People,” 1914 at the Getty Museum can be viewed here; see also this version with the same title.

(2) Carl Moon, “Primitive America,” 1914, also at the Getty Museum.

(3) Carl Moon, “Man in Diné (Navajo )Dress,” 1907, National Museum of the American Indian; and from the same collection: Carl Moon, “At the Well of Acoma” 1910.

(4) Some of the other photographs in this remarkable series, held by the Library of Congress, can be viewed here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rick Halpern is an historian and photographer based in Toronto. In recent years he has been writing about the history of visual culture, especially photography, and the way it has shaped our understanding of identity and place. His photographic practice focuses on three main themes: urban life, travel, and food.

Robert Wilson

April 28, 2021 at 20:14

Excellent piece!

Bri

February 26, 2025 at 16:46

Theyre just photos from the western expansion

Bharat Patel

April 28, 2021 at 21:00

Excellent article throwing good insight into the photography from some great passionate photographers. Though some of the images would be contrived in present views they still have contributed significantly to what would otherwise would have left the world ignorant of these great native people. When these images where taken there was little definition of documentary photography. I am in the process of printing E. Curtis’s images in pure carbon inks in an effort to preserve them even futher!

Chris Villiers

April 29, 2021 at 09:30

Thank you for this series of articles. I always find them interesting, educational and help me explore both the technical and artistic components of photography. And with all the recent controversy swirling around Edward Curtis and his peers, your broad and indepth view of their work is a welcome antidote to the typical commentary that currently surround them.