My last column explored the way in which photography played a role in documenting and interpreting the American West at the turn of the last century, depicting native peoples as a “vanishing race” whose disappearance allowed for a final stage in the colonization of western territory. This article continues the theme of photography’s role in the colonial project by looking at the uses of the medium in America’s new overseas empire, acquainting Americans with their new subjects and contributing to the categorization of these people in a racial hierarchy that was very different than the black-white binary to which they were accustomed.

When Spanish forces in Manila surrendered to Admiral George Dewey in 1898, most Americans had little knowledge of the Philippines, its peoples, culture or economy. With the nation’s attention focused on the Spanish American War’s Caribbean theatre, the Philippines remained secondary, at least until Emilio Aguinaldo’s independence movement turned its guerrilla war against the American occupiers and necessitated the commitment of over 10,000 troops. Even then, with newspapers carrying stories about the conflict, Americans remained indifferent and ill-informed about their new colonial subjects.

However, within a short time, two groups of Americans discovered that there was value and a great deal to observe in the Philippines, and that its diverse population would make ideal subjects for their twinned enterprises: anthropology and photography. This historical conjuncture at the end of the nineteenth century was both significant and auspicious. Anthropology was in its infancy when the Philippines became an American colony, while photography was moving rapidly to maturity. Bulky, tripod-fixed cameras using glass plates, adjustable lenses, and long exposures produced the era’s high-quality photographs, but inexpensive, portable cameras with rolled film – such as those manufactured by Kodak – allowed non-professionals to capture acceptable images. Both tools proved important as early anthropologists took up the task of documenting and classifying the flora and fauna, as well as the people, of Pax Americana’s newest territory.

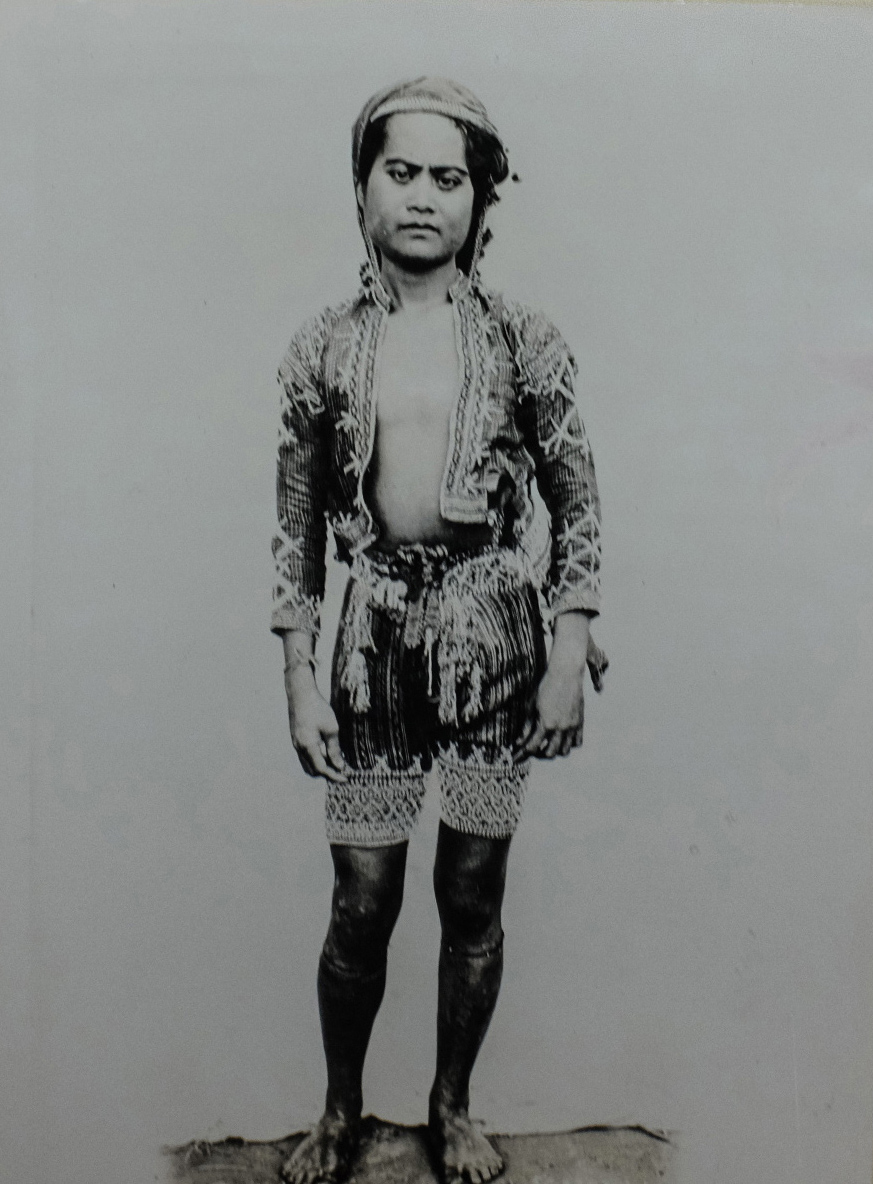

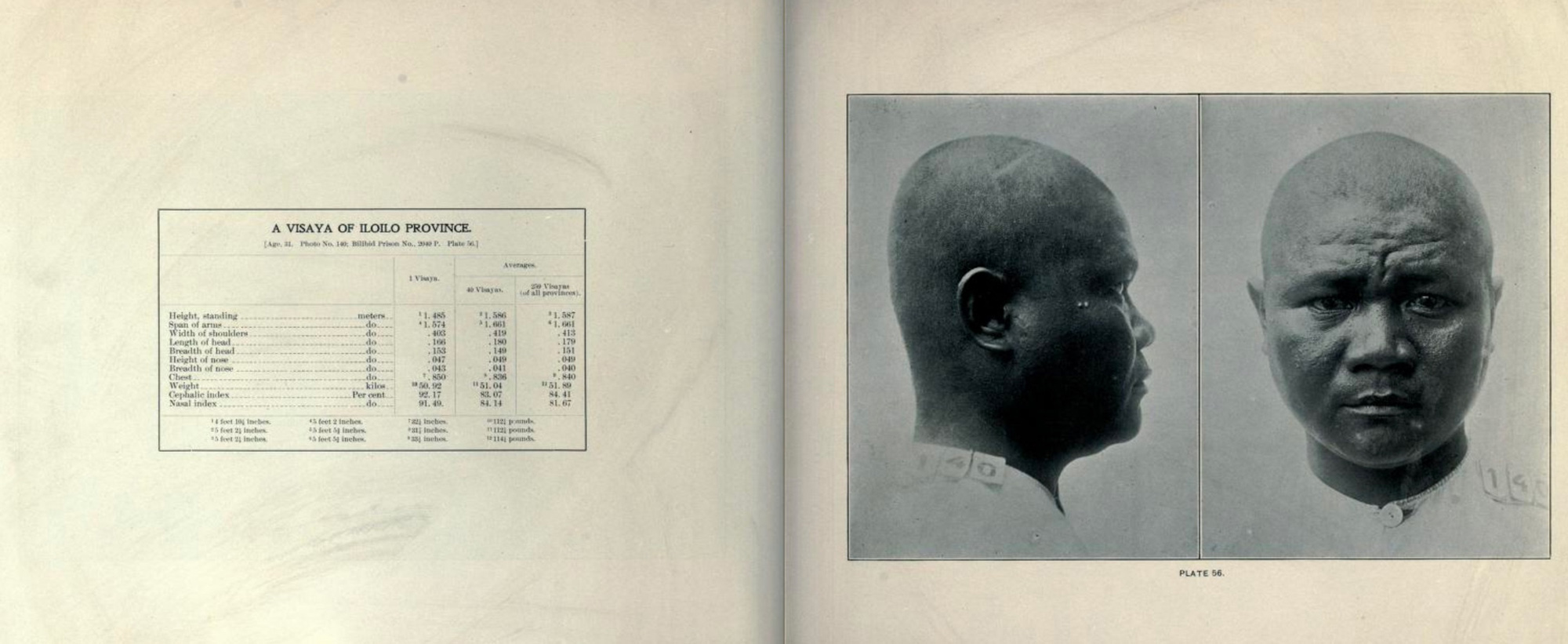

A main concern of early anthropology was documenting racial anatomy. Many of the first American photo-anthropologists in the Philippines relied upon the camera to accurately capture body types and physical features, presenting these images as objective facts in lavish scientific and popular publications. One extreme study examined Filipino ears, taking careful posed photographs of hundreds of living subjects along with dozens from morgues. Another early contribution to the field used inmates hailing from different geographic regions incarcerated in Manila’s Bilibid prison to produce an album of mugshots deemed “Philippine Types” (see Figure 1 above). To a US public well steeped in the black-white domestic binary of Jim Crow, racial identities in the Philippines were confusing; these writers sought to untangle a messy foreign reality and present the people of the Philippines in neat racial categories.

Less well known is a sizeable body of photographs that approached race through a cultural lens. Scientists and photographers recorded images of native peoples’ clothing, jewelry, musical instruments, tattoos and body markings, as well as their rituals, dances, and hunting practices. These images, too, were used by photo-anthropologists to make statements about the way race “worked” in a seemingly hostile and exotic land.

The photo-anthropological component of that project began in the American West during the preceding decade. Under the aegis of the United States National Museum (later the Smithsonian Institution), the Bureau of American Ethnology documented what it believed to be a “vanishing race” of native people vanquished by the military following the Civil War. Producing some of the most important photographs of life on the plains and far west, photographers and early anthropologists employed by the Bureau worried at century’s end that with the closing of the frontier their work would conclude. War with Spain and the acquisition of overseas colonial territories gave them a new lease on life. Bureau leaders embraced the work of empire. They drew up an action plan that proposed the extension of its activities into the Pacific that would allow anthropology to flourish and racial science to advance. This, the Bureau’s Director wrote “affords a great, and probably a last, opportunity to witness and record the intermingling of the racial elements of the world and the resultant physical, mental, moral, and pathological interactions in all stages and in every phase.”

While the cultural approach to documenting colonial subjects understood race as fluid – and hence in need of scientific explication – racial morphologists operated with a more fixed understanding. They also found opportunity within the National Museum with the 1903 creation of its Department of Physical Anthropology. Both branches of the Museum sent personnel to the Pacific. In addition, they supported colonial photography projects and assembled sizeable photographic collections. Around the same time, the colonial state in the Philippines began generating its own visual materials in an effort to document the “non-Christian” tribes of the region. Taken together, these images, the human taxonomies they purport to represent, and the way they have been catalogued, all speak to the American obsession with race.

National Archives)

Consider this striking photograph of a Bagobo youth (Figure 2). At some point in the processing of the collection, not content to allow the image to speak in unmediated fashion, an official typed an interpretive note on the sheet upon which the print was affixed. The apparently objective appearance of the Bagobo is misleading, the commentator noted:

…to judge from his wistful expression and cupid lips, one would get the impression that he was effeminate. To be truthful, he is a valiant fighter and cruel to the extreme. When armed he carried a strongly tempered steel barong and kris dagger…The barong is a heavy weapon, razor-edged and the fighter can, with a single blow, halve his opponent at the waistline. To cleave the enemy to the neck is child’s play for the meek appearing pagan.

This gendered corrective both cuts against the grain of the image’s natural properties – there is little that strikes a modern viewer as particularly feminine in the man’s pose, demeanor, or dress – and speaks to colonial assumptions about the Mindanao region’s people. The move to graphic violence in the addendum communicates an ambivalence about the trustworthiness not just of the photographed youth but the Bagobo as a whole.

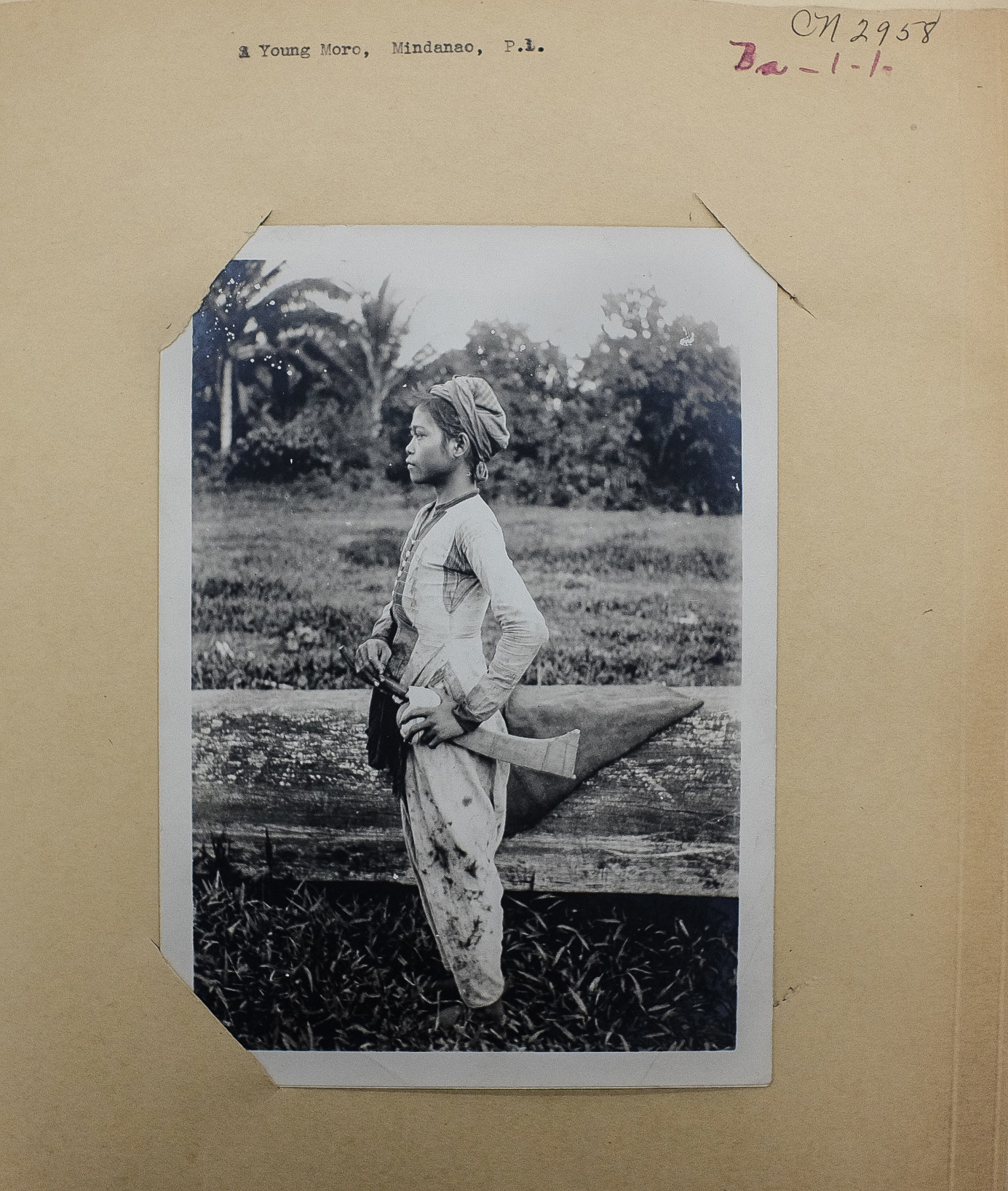

Historical context helps explain this intervention. The southern portion of the archipelago posed a challenge from the start of U.S. involvement in the Philippines, as both the government in the region and various tribes located across the southern island transferred their armed resistance to Spanish rule to the Americans. After a short-lived peace collapsed, an insurgency, known at the Moro Rebellion, raged until 1913. While the expedition that gathered these photographs was not a military venture, it took place in an atmosphere of war. The photos reveal a fascination with weaponry, and many depict bolos, kris daggers, barongs and other swords (see Figure 3). Moreover, expedition members would have been well aware of the savage fighting that characterized the rebellion from lurid newspaper accounts as well as from conversations with soldiers.

Comments and notes on the images depict an exotic and potentially dangerous population. For instance, a portrait of a man taken near the town of Zamboanga carries the note “dressed like a pirate;” another, shot near the provincial capital of Jolo, captures an older man with the handwritten observation “not as infirm as appears. Was carrying a knife.” A Manobo man’s headdress is noted for its elaborate decorative feathers, but the commentator has added, “a warrior who has killed.”

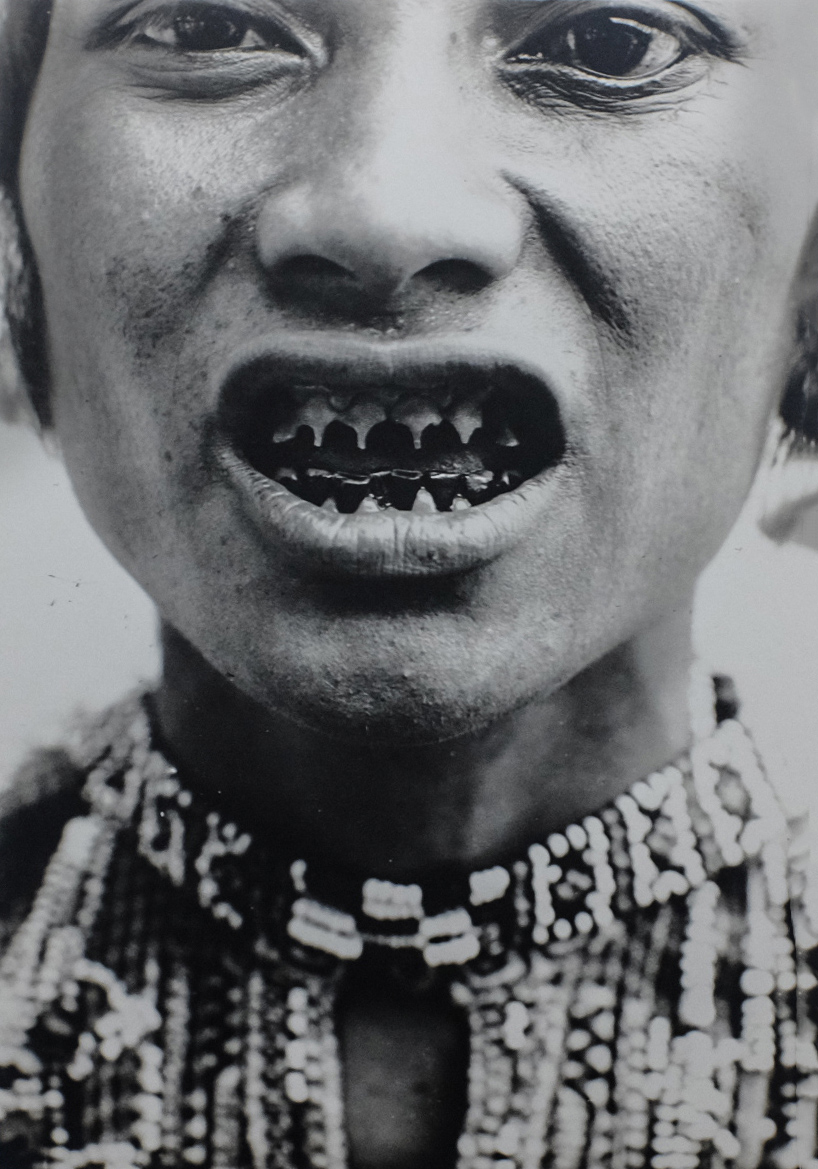

Particularly startling is a photograph taken in the Davao region of a Bagobo man’s filed teeth (see Figure 4). This image stands out for its radical cropping and close focus. Again, no context is visible, and a shallow depth of field allows the two rows of pointed teeth to dominate. A beaded choker and shirt, dark skin with visible pores, and almond eyes of different sizes convey a primal indigeneity. Lest there by any ambiguity about the subject of the photograph, an appended note directs our gaze: “note the filed teeth.”

Clearly the elaborate adornments that royalty and warriors wore in the southern provinces attracted anthropologists, photographers, and explorers titillated by exotic exploration. Many of their photographs capture this aristocratic level of society bedecked in their finery. Notes and captions often remind viewers that these are, in fact, violent men. Visually, this kind of message receives constant reinforcement. In multiple clearly posed photographs, the subject rests a hand on a sword or knife, suggesting that outlandish costumes of this sort accompany lethal force (see Figure 5).

By the mid-1910s, the Muslim insurgency in the South had died down and the independence movement elsewhere had laid down its arms allowing the U.S. occupation to settle uneasily into a more stable mode. American photography in the peacetime Philippines shifted its focus, continuing to document the more than eighty recognized tribal groups across the islands as well as capturing images of plantations, manufacturing, and handicraft production. This economic turn correlated to the colonial enterprise’s next phase: developing export industries and attracting capital investment. Curiously, despite a population of over ten million, officials spoke frequently of a labor shortage that they feared might cripple the Philippines economically. To help avert a catastrophe, they pressed photo-anthropology into service.

From the start of the ethnological enterprise, costume and clothing formed an important subject for photographers. Now, as officials sought to understand which groups of Filipinos best would be suited for different sorts of labor, they decided that tribal dress could hold the key. This exercise was made possible, in part, by the proliferation of images in several collections in both the Philippines and the United States.

A series of photographs lent by the Manila’s Philippine Bureau of Science to the U.S. Bureau of Commerce serves as an excellent example. Some of the images are like those noted above that were shot in Mindanao in the early 20th century. They depict regional elites, usually identified with tribal names on the front mount, but carrying interpretive text about clothing and class on the reverse side. Three Moro men appear in one such photograph (see Figure 6). They are well dressed and casually posed, looking both poised and confident. The note on the back details the fabric and make of each costume before going on to note that although these “are by no means laborers” the average working man in the southern Philippines would wear colored striped drill trousers similar to the man on the left, minus the black coat and white shirt. In another, a lone barefoot worker awkwardly poses for a side view, a dirty long-tailed shirt hanging over bunched trousers. “A Filipino laborer of the lowest class” reads the note on the back. From the same series. a dockside scene on Manila’s Pasig River centres on three Americans, filling the centre of the frame in the head-to-toe white suits of the tropics, but the annotation focuses on the fisherman well off to the side, making note both his “day work costume” of blue denim and his nightwear overshirt known as a camisa de chino, which he has donned “to see the town.” Again, appearances can deceive in the colonies, but photo-anthropology can decipher labour market position and class just as surely as it can read race so far from home.

Photographs such as the ones discussed here derive their significance from the way that they objectified their subjects and then were used to produce knowledge for use by colonial powers. Posed, prodded, and placed in specific postures, the Filipinos, whose images were made by early twentieth century photo-anthropologists, tend to be historically mute. In hundreds of photographs in multiple collections, they appear as the raw materials of a process of colonial rule that involved silencing their own narratives. Yet every now and then one encounters a flash of agency, not quite a voice, but a sense resistance to the photographic moment.

National Archives)

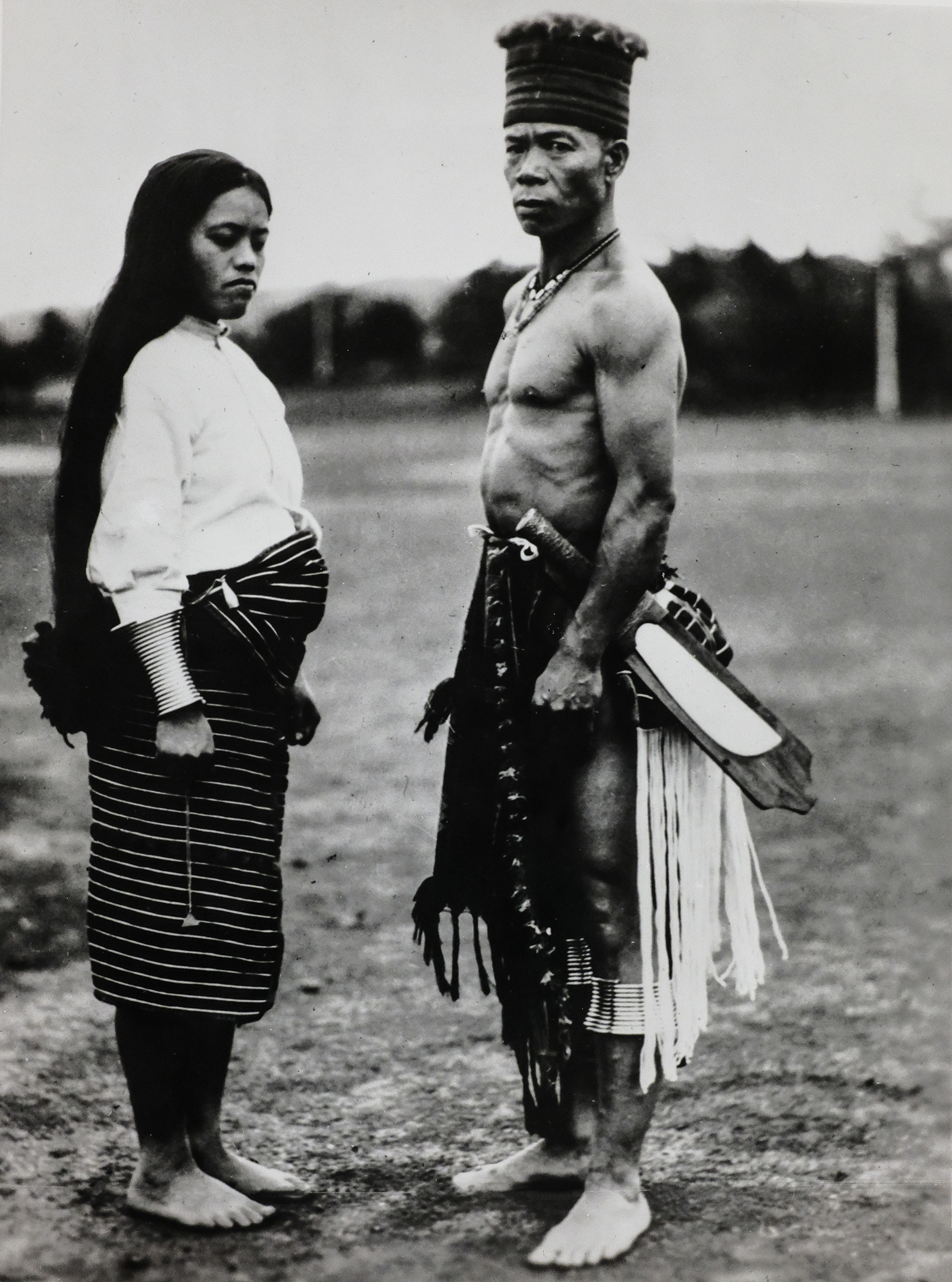

Let us close with the couple pictured in Figure 7. The series from which this photograph is a part also shows them in a traditional dance and posing candidly, looking away from the camera. A note identifies the man as “probably a priest.” But in this image, their postures, their facial expressions, and clenched fists make clear their displeasure with the documentary project. They are not willing subjects and, in this captured moment, resist being transformed into objects of colonial anthropology.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rick Halpern is an historian and photographer based in Toronto. In recent years he has been writing about the history of visual culture, especially photography, and the way it has shaped our understanding of identity and place. His photographic practice focuses on three main themes: urban life, travel, and food.

Bruce Caron

June 3, 2021 at 23:39

Lewis Hines one of my favorite photographers due to his instrumental work in uncovering the abuses of child labor .