Perhaps it’s a bit like golden hour.

Sunlight falls on us all day long. Yet, for just a few moments toward the end or beginning of each day, it’s different. It’s better. The whole world suddenly takes on an atmosphere that seems more illuminating, more profound, more beautiful. Nothing has really changed except the angle of the incoming light. But that change is everything.

“Ruth Orkin: A Photo Spirit”

Published by Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2021

review by W. Scott Olsen

Ruth Orkin: A Photo Spirit is a wonderful book, and I wish I had a way to explain why these images are more illuminating, more profound, more beautiful than so many others. It might just be a way of seeing. It might be a great deal more.

If you are a photographer, you need this book. Even if you are not a photographer, you will enjoy every page.

© Orkin/Engel Film and Photo Archive; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

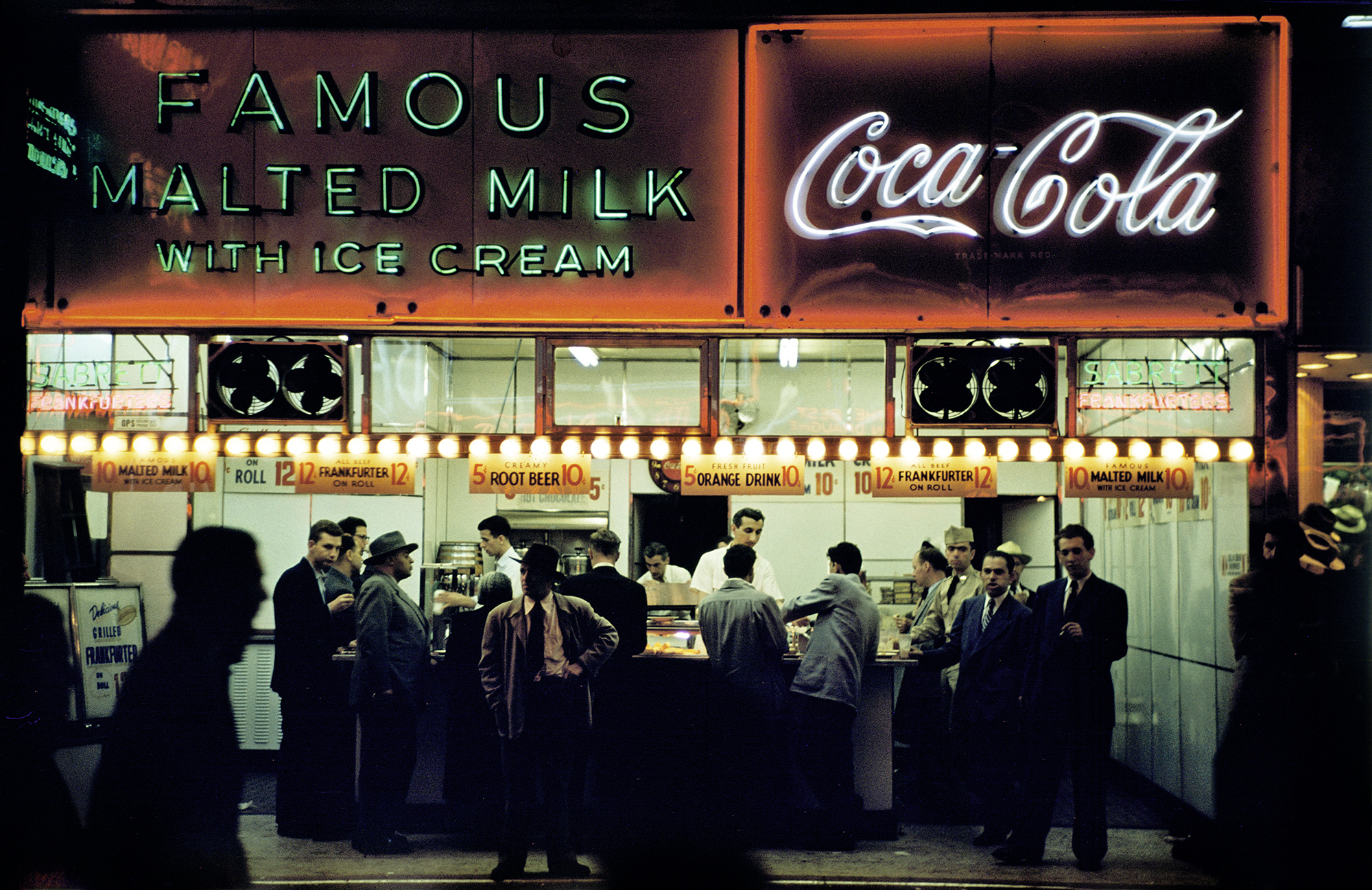

Perhaps because of her early interest and work with movies, Orkin’s images often have a cinematographic feel. Whether it be in the lighting, the angle of view, the closeness to the subject, or the arrangement of subjects within the frame, the images have a gravitas that comes from storytelling.

Images as simple as a row of snow-covered cars and stoops in New York, or young girls reading comic books in the West Village, or two American tourists at a sidewalk café in Rome, all have that wonderful framing that comes from understanding the moment on film is actually part of a larger, ongoing story. Her portrait of “Leopold Stokowski Conducting at Carnegie Hall, New York City, 1940”, for example, is taken from off stage, the composer framed by balcony box seats and a soaring pillar, the silhouettes of people and equipment in the foreground and the harsh lighting straight out of film noir. It’s an eerie, unique, and fine picture. Orson Wells and Alfred Hitchcock would have loved it.

© Orkin/Engel Film and Photo Archive; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

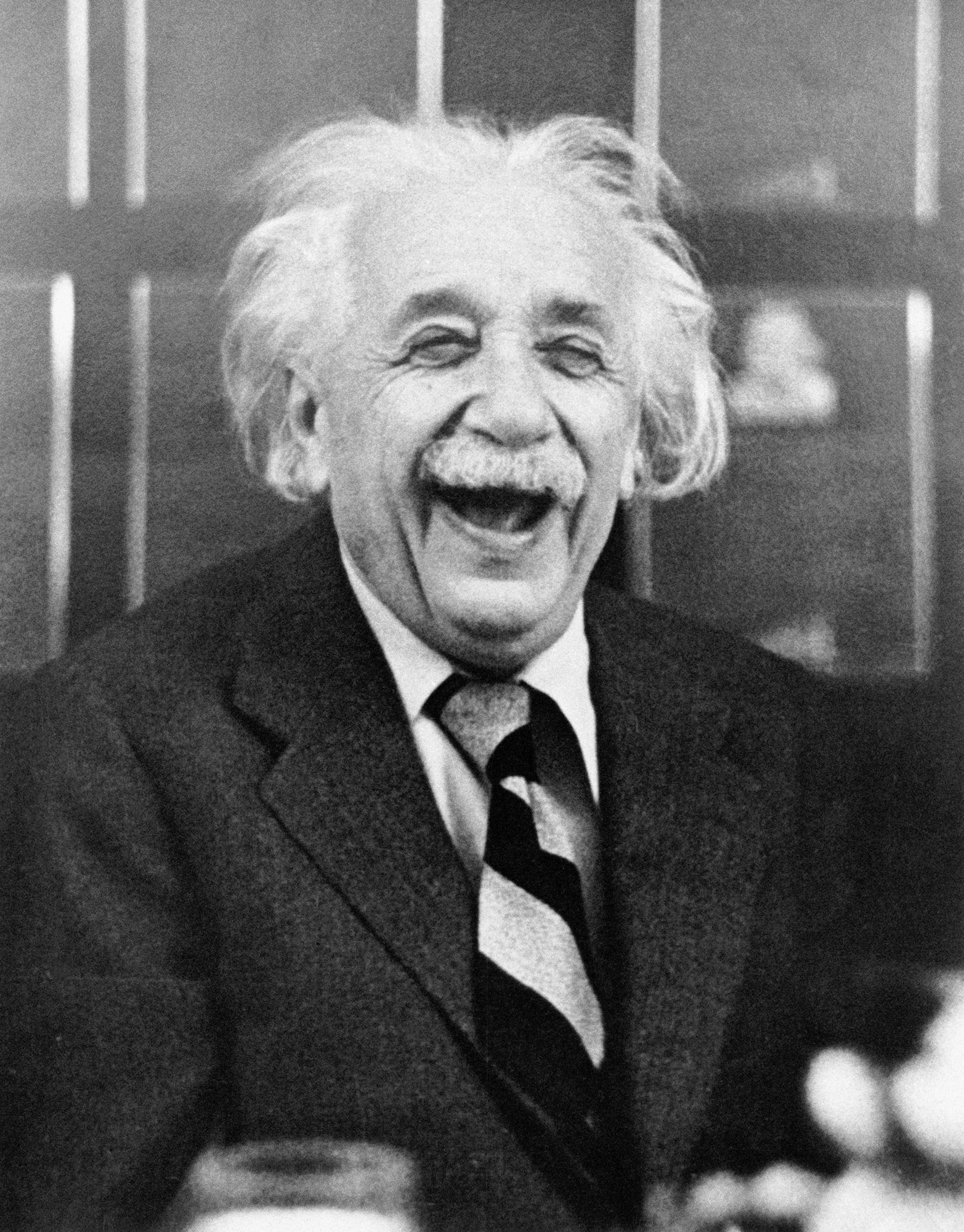

Her images of celebrities are most often candids – Albert Einstein laughing during a lunch at Princeton, Joan Crawford at a party, Lauren Bacall in a hotel room, Alfred Hitchcock on the set of I Confess, Tennessee Williams on the set of A Streetcar Named Desire, Robert Capa at a café in Paris, Lucille Ball on the set of I Love Lucy. Orkin writes that she wanted to be unnoticed when she was shooting, to the point of missing a shot if people could hear the shutter, and with that technique her portraits reveal famous people in possession of some other thought. They are not posing for her. They are honest.

© Orkin/Engel Film and Photo Archive; VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2021

There really isn’t an ounce of cynicism anywhere in this body of work. There is very little irony, either. What there is, is usually celebration. Even the picture of a young woman holding a child, a number tattooed on the woman’s arm, is an image of surviving love.

The book contains a great many street photographs in the way we think about them now, and there are also street photographs which are staged, set-pieces meant to evoke more than document. In the way that fiction can be more true than nonfiction, if we’re speaking about moral truth or social truth, the set-pieces here are precise.

Of course, the shots in Florence in 1951 are what made Orkin a superstar.

The most famous shot, simply captioned “American Girl in Italy, Florence, Italy, 1951” (see the featured image above) shows her friend and model Jinx (Ninalee Craig) being catcalled by a group of men on a street corner. The image was a setup, and a second take at that. It appeared in the September 1952 issue of Cosmopolitan, but a quarter century later it saw another life as a poster and then the spark for debates about truth in photography, about gender roles and gender politics, about social norms and behaviors, and a host of other topics.

The image tells a story. It is decidedly true, despite being fiction.

It is unfair to reduce a photographer’s reputation or oeuvre down to one or two images. And this book does an excellent job of portraying the scope of Orkin’s work. There are the famous sequences of images titled “Jimmy Tells a Story, New York City, 1947” as well as “The Card Players, New York City, 1952.” There are images from the set of her film, “Little Fugitive.” And there are all the rest, equally good. One hundred and eighty images are black and white. There is a center section of twenty images in color.

© Orkin/Engel Film and Photo Archive; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

The book is not chronological. Instead, the images are grouped thematically. People in a park. People in Venice. Celebrities. New York. The arrangement allows us to consider each image not only on its own, but also in context of the place and time revealed by the group.

Orkin’s life seems larger than life. Not only did she bicycle across the United States at age 17 (there is a remarkable image of her sitting on a single speed bicycle with a slightly damaged front fender), she was the first messenger girl at MGM, hired in 1941. Her mother was a silent-movie star. And then she quit because the union did not allow women. She joined the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps. Her first professional assignment was from the New York Times in 1945, to photograph Leonard Berstein.

© Orkin/Engel Film and Photo Archive; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

Ruth Orkin: A Photo Spirit opens with a brief introduction and welcome by Mary Engel, Orkin’s daughter. This is followed by an essay from Kristen Gresh, Senior Curator of Photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which gives an overview of Orkin’s artistic history and articulates Orkin’s position as a woman in the first half of the 20th Century, working in a field dominated by men.

The book also contains excerpts from Orkin’s unpublished autobiography which often reveal a curious and confident young woman intent on developing her knowledge and skills. For example, writing about her time as a messenger girl at MGM, she says, “What influenced me to become a photographer and later a movie-maker? Certainly working at MGM studios for six months. As a messenger being sent here and there I saw a lot more of the studio operation than almost any other employee (except other messengers). And I had a tidbit of lingering where things were interesting or I thought I was learning something.”

“Not only did I have a lot more freedom than secretaries, wardrobe or make-up women, or even a script girl (who was on set all day),” she continues, “I had the attention and help of all the men in the technical departments (because that’s where my interests lay). In how the cameras worked, in the moviolas, the sound stage booths, the music editing screening rooms. On my lunch hour I was taught how to use the moviola and given film cans with dozens of well-known montages (all coiled up in little rolls) to study. It was fun to read the scripts and production notes and then happen to pass by while a certain scene was being filmed.”

In a section called “Being a Woman Photographer” she writes, “Do women see differently than men? Of course we do because we’re different people. Everybody sees differently from everybody else. Partly it’s because you’re tall or short, or because you’re a minority or a non-minority. All the things that make up a person make their view of the world and part of your person is your sex.”

© Orkin/Engel Film and Photo Archive; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

In a section called “Noticing How Light Fell” she says, “The first time I remember thinking about how light fell and the angle on a person’s face I was sixteen and sitting on the Eagle Rock streetcar on Colorado Boulevard. There was an attractive boy sitting opposite me and I said to myself, ‘Now, if he would just move a little to the left and tilt his head down, I could get a perfect portrait of him.’”

The text in this book is both brief and insightful. It gives the images a bit of needed context in 2021. But the book’s strength is solidly in the wonderful images.

Orkin died in 1985, from cancer. She was 63 years old. The publication of the book coincides with her 100th birthday. As Mary Engel writes, “This book you are holding is her first major publication in forty years – she would have loved it!”

I love this book. Every image has a power to it that, as a photographer, I find both humbling and inspiring. This book is one of the necessary ones.

© The Estate of Alfred Eisenstaedt

A note from FRAMES: if you have a forthcoming or recently published book of photography, please let us know.